October 1, 2013

[berkman] Molly Crabapple on art when images are ubiquitous

I’m at a Berkman lunch where Molly Crabapple [twitter:MollyCrabapple] is giving a talk titled “Art in the Age of the Ubiquitous Image.” Tim Maly introduces Molly as a “hustler,” in the good sense. After Occupy, she “hustled her way” into Gitmo. She and Tim were “Artists are the most lucky little foofoos in the world. We spent a century excusing every drpravity if with ‘But we’re an artist.’ …The best individual

|

NOTE: Live-blogging. Getting things wrong. Missing points. Omitting key information. Introducing artificial choppiness. Over-emphasizing small matters. Paraphrasing badly. Not running a spellpchecker. Mangling other people’s ideas and words. You are warned, people. |

She begins by telling us about the only two people who have ever gotten angry at her drawing their picture. First was a religious person in Morocco. She wanted to distinguish herself from the culturally arrogant tourists, so she’d sit on a sidewalk and draw. She made friends, except for one guy who looked at the drawing pad and tore it to pieces. The second was a NYC police officer. She was sitting in a court with Matt Taibbi and watching poor people being shaken down for offenses such as riding a bike on a bicycle. A court officer saw her drawing him and said that anyone looking at him is “asking for trouble.” “Drawing can mock power,” she says.

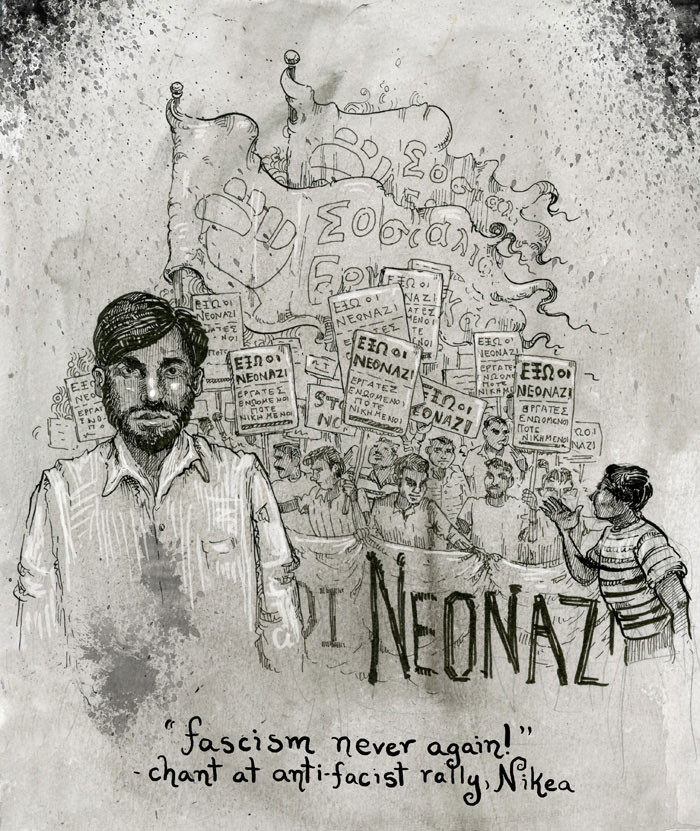

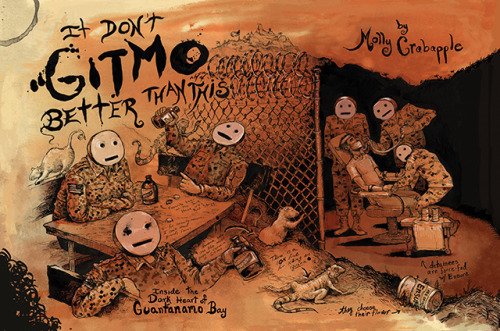

She says she’s an artist in the old sense: She puts paint on a surface until it looks cool. She also does illustrated journalism. She shows drawings from Zuccotti Park during Occupy. She used her sketchbook to show that people were not in fact “dirty hippies.” She went to Athens to show what life as like with the rise of fascism during the Eurozone crisis. At Guantanamo, she drew happy faces on the guards because you’re not allowed to draw their faces. If she’s censored, she wants to show the censorship.

When she was young, she longed for the days when artists dominated image-making. Before cameras, artists drew whatever needed reproduction. She shows a plate from Goya’s The Disasters of War to show how art can editorialize in a way that photos can’t. Drawings can show the truth of what happened.

Another example from the Paris Commune: a woman guarding a hotel. Otto Dix’s drawing of a veteran with skin grafts shows “only the essential, not the extraneous. Even fashion was the domain of artists before photo. E.g., Kenneth Black’s drawings.

But photography has an advantage in that we assume what we see is true. E.g., Goya’s execution painting never actually happened. But now everyone has camera phones, and every is being surveilled. There are more images now than ever before in human history. Where does that leave art?

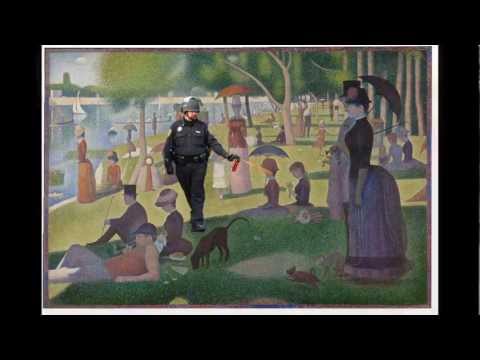

There are two symbols of global rebellion: the Guy Fawkes masks and arms outstretched holding camera phones. When a kid got beaten up, a crowd of peers formed with their camera phones out. “You will become an Internet meme,” they were saying. Camera phones make people accountable. The Net takes every image that has resonance and spits it back out transformed. Officer Pike, who pepper-sprayed protesters at UC Davis, has become an Internet meme.

The flip side is that the government now can view us unceasingly. Soon the line between what we’re viewing and how they’re viewing us is blurred: the gov’t views us through our phones by which we view our world. Some of the coolest art plays with this. E.g., William Betts does paintings based on CCTV stills.

But as photography becomes ubiquitous, our faith in its truth is chipping away. E.g., Kerry used a photo of wrapped bodies to justify a strike on Syria, but it was taken in 2002 in Iraq. Photos are not the truth and they never were. And even when photos are indisputable, it’s not enough. Police still get away with murder. The videography is less important than the power structure.

We live in a world where everything is captured, so what’s the point of my drawing things? What possible significance can it be? “Or am I just picking scabs? It’s just my personal compulsion?”

Art has always absorbed new tech: Big canvases during the Renaissance, use of the camera obscura. She shows a drawing of the Golden Dawn fascists being confronted by local shop owners. For the drawing, she took many many photos, they looked online to find more posters, and you end up with a drawing that’s a collage. You never now have trouble figuring out what thnigs look like. “Even that is a gigantic change brought by the Internet.”

One of her projects last name was “Shell Game“: taking the Occupy protest and Arab Spring and retelling massive “alter pieces” for them, votives. But when she was drawing them, she wasn’t just drawing what was in her head. She was researching them the way journalists do. She interviewed people. E.g., a Tunisian blogging collective told her that the term “Jasmine REvolution” as “hideous Western branding” and please don’t use it.

She shows a Rembrandt drawing of Haksen the elephant. IT was the first time people had seen it. Now, the image of elephants has become ubiquitous.

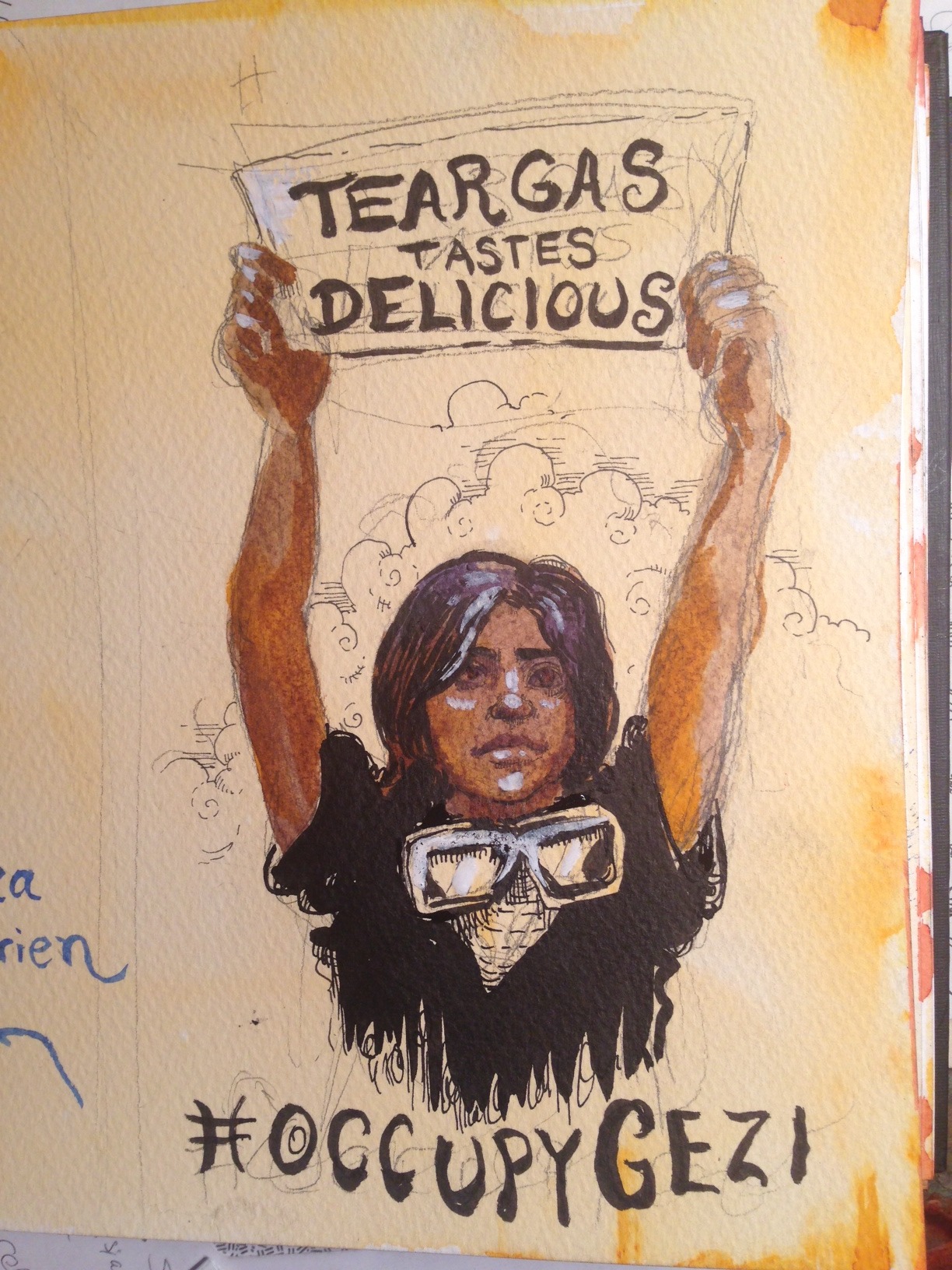

Her friend Paul Mason when toOccupy Gezi. He took photos. She drew them, but only after crowdsourcing the translation of signs on Twitter.

Guantanamo is simultaneously the most private and the most surveilled. Every cell has a camera checked every 3 mins. Even the location of the cameras is secret; if she drew them, the sketch would be confiscated. She spent 2 wks there on 2 differenttrips. “What became important to me was to draw the censorship.” She wasn’t allowed to draw anyone’s faces, even though their identities are well known. So she had to scratch out the prisoner’s faces. [The face-blocked prisoner drawings are amazing.] She also isn’t allowed to draw anything that would give a sense of the layout of the camp. The Opsec briefing tells you the only three angles you’re allowed to draw from.

She shows a drawing from life of the Chelsea Manning verdict.

There are other reasons people might not want to be drawn. She shows a drawing of Syntagma protesters with prominent facial scars, so she drew him holding his logo over his face. She shows a drawing of Maxence Valade who had an eye shot out. He let her draw him.

There are places where there are just no cameras. She was jailed for 11 hours during Occupy. It was incredibly boring. She drew pictures in a styrofoam cup and tried to commit the cell to memory. When released, she drew it.

Joe Sacco has drawn images of Palestinians being interrogated. “Artists can take memories and make them real.”

Access can be taken from us. The Internet can be shut off. They can take your camera phone. But drawing cannot be stopped. E.g., David Choe was in solitary for a while. He had nothing to do but draw. He drew with soy sauce and his own urine.

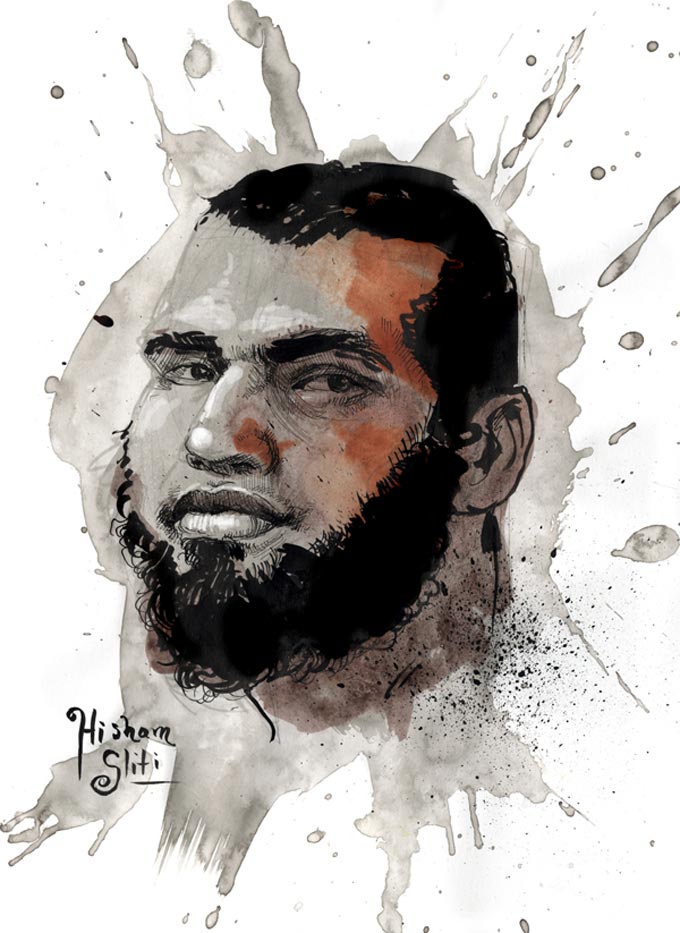

“The art of drawing something sets it apart.” She shows the official Red Cross photo of Hisham Sliti in Gitmo and then her drawing. “I wanted to set him apart. I want you to remember who he is.”

“We need the chaos of multiplicity. We need raw data. We need everything. But we also need the singular. And that’s what artists do. We need people who can be stealthy and subtle, and can go where photographs cannot.” Visual art has no pretense of objectivity. “Images have power.” An illustrator in Syria had his hands broken. “Images get past fatigue. Images get past the raw edges of your heart.”

Q&A

Q: You’re comparing image production before the flood of images and now. How about how crowds are pulling from the flood now?

A: Artists are always of their age. I use the Internet as an artist, but also to look for steak in the morning to eat. We dive into the multiplicity, pull out the singular, and then that’s pulled back into the crowd.

Q: The Guy Fawkes mask comes from V for Vendetta. The image is owned by Warner Bros.

A: And there’s also the real Guy Fawkes, a Catholic subversive whose politics none of us would find inspiring. Then there were the folk festivals. Then V for Vendetta, retaking the mask as a symbol of rebellion, but more as a carton symbol. Then you have 4chan and Anonymous bringing it back to its original meaning of rebellion.

Q: How do your images find a way through all of that. You talk about using the network as a repository of possible influence, as an expanded canon of images one might interact with. Once an image is produced, how does it find its life in the world?

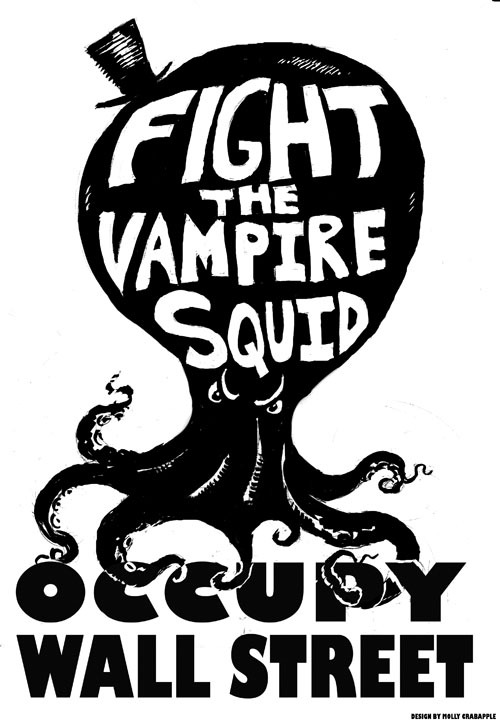

When Occupy Wall St. hit, it had no images. I did a vampire squid. It showed up on protest signs. Schlocky t-shirts were selling it. The image had a life. She also did a free Pussy riot poster. A week alter there was an Al Jazeera news piece saying “Some people will make money on anything,” focusing on Russian t-shirt makers making unauthorized copies. Madonna tweeted it, and Time said she made it. Memes show up in burlesque shows. Many bad tattoos based on her art. (“That always hurts and artist.”) “The network eats all.”

Q: Do you get criticism from journalists for not being fact-check-able?

A: I work with fact-checkers when facts are involved. When I can’t take photos, I hew as closely to reality as I can. But there’s always an editorial slant to any photo or drawing. E.g., the photo of the Vietnamese police officer executing a suspect has an emotion.

Q: Who are you drawing your political art for?

A: One of my problems with political art is that it draws on the same canon: Soviet, black and red. Very cool. But people know immediately if it’s for them. I want to make art for people who don’t think political aesthetics is for them. Maybe they relate more to fairy tales, or…

Q: Has the nature of cooptation change? What’s the difference between an image being made commercial and an image becoming a meme?

A: In some ways I think it’s cooptation. If someone used my Pussy Riot illustration to advertise their t-shirt shop, with tags like “glam,” yeah, that’s cooptation. Political campaigns do this, as when musicians objected to their songs being used to introduce Sarah Palin. You should fight back against that, but it happens because the world is intensely interconnected.

Q: In the 19th century there was an exhibition of dioramas. The Beehive Collective is doing something similar. Do they understand the diorama? Can we revivify it?

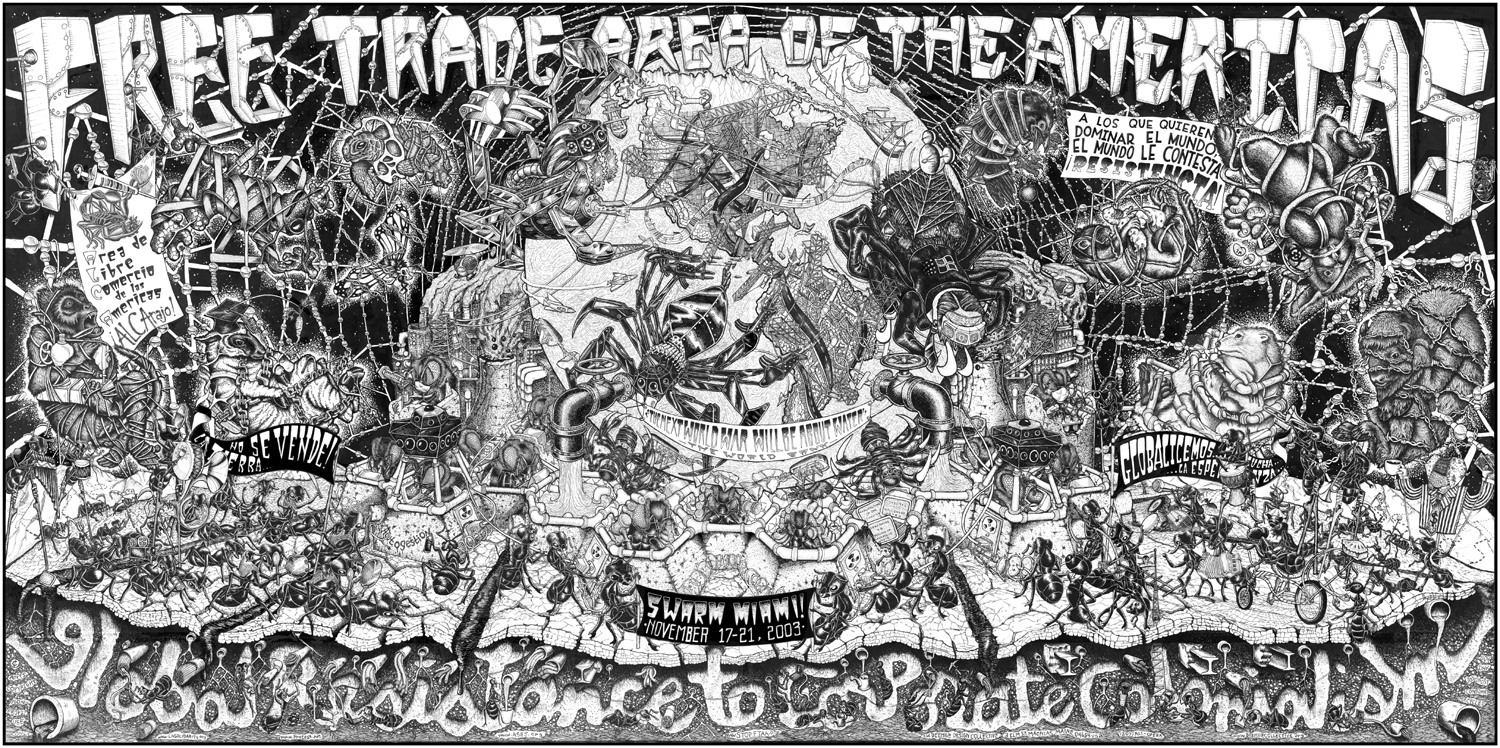

A: The Beehive Collective does this incredibly detailed, gigantic pen and ink drawings of subjects like strip mining, environmental policy, etc. The topics are very complex. They go to the local areas and revise and revise their thing until the locals think it’s a truthful representation. They are telling very complicated stories without depending on language or literacy. It’s an intensely important thing to do.

Q: Do you do that consciously with some of your larger displays?

A: Yes. I always try to get beyond language. One of my first jobs was as house artist at a swanky club. That was my lockpick. Art is totally a lockpick.

Q: What’s been most jarring or unexpected for you?

A: Guantanamo is the most bizarre and jarring place I’ve ever been to. It’s a cheerful American town with a Macdonald’s and karaoke bar, next to a super-max prison dedicated to guarding 169 middle age guys most of whom have been cleared. There’s a pantomime of security there. Everything says that you’re about very dangerous people, but it’s a small American town.

Q: So it’s like North Korea.

A: Exactly.

Q: The network mainly displays images at 19″ maximum usually, but you draw much bigger than that.

A: I want to do art that’s really big. It affects you differently. It surrounds you. It’s a dominating relationship. But it doesn’t reproduce on line. Diego Rivera was much more known in his time, but now Frieda Kahlo is. That’s because you have to go to a Rivera to see it in real life, but Kahlo reproduces well on a smaller screen. So, how do you take really really big life and give it a digital life that’s somewhat as interesting as real life is.

Q: Panorama stitchers? Microsoft has one that lets you zoom in or out. E.g., the AIDS quilt. Cf. gigapans.

Q: What does the physicality of the drawing do for you.

A: There’s an egomaniacal bit of artists. When I make a large painting, I feel like I’m falling into them. My next project is going to be a show of large paintings about hackers. I want to do a 20-foot wide painting. It’d be bullshit to do something on the network and not have it be on the network.

There are things you can’t see online. I use zinc white, which is toxic, but it’s super transparent, warm white. It doesn’t reproduce in photos. There’s a lot of art you can’t get from photos or on the Internet. We forget that there are all sorts of things you have to be there to see.

Q: The way that experience gets remediated and ported back out to the Internet, it can underscore that they can’t be reproduced on a mobile device.

Q: There are places you can’t bring cameras onto. E.g., courtrooms.

A: I don’t know what they don’t allow cameras. It seems like a rule from wayback when camera flashes made smoke. I know that with the KSM courtroom, they didn’t want any of their cameras shown, or the doors, or the faces. It would have been impossible to get photos there. I think it’s misguided but I also sort of like it because it allows one place where my people can king.

Q: Do you ever encounter people who area trying to learn to draw so they can get around censorship and share emotions?

A: Prison art. I profiled a Gitmo prisoner who learned to draw for that reason.

Q: Dr. Sketchy?

A: Dr. Sketchy is my alternative drawing class done in a bar with drag queens and models, done in a subversive way. I want people to learn to look without asking for permission. Artists are the creepiest people around [laughter]. Drawing is a way that I was allowed to look, where looking wasn’t taken as an invitation but as something else.

Q: Susan Sontag says that people thought that showing violence would lead to peace, but that images of violence in fact can provoke more violence.

A: That happens when pictures of atrocities can spur revenge. But drawings can also get past people’s defenses. But maybe I’m just being hopeful.

[Great and very special presentation. Thanks, Molly!