How word processing changed my life: A brief memoir

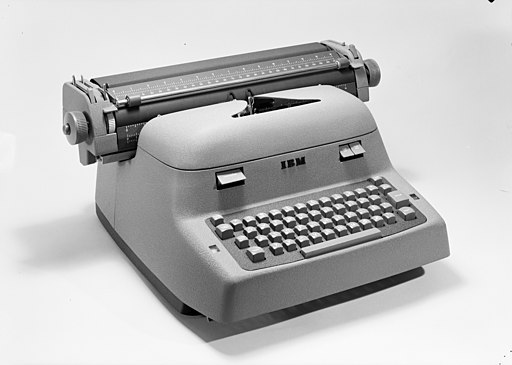

I typed my doctoral dissertation in 1978 on my last electric typewriter, a sturdy IBM Model B.

My soon-to-be wife was writing hers out long hand, which I was then typing up.

Then one day we took a chapter to a local typist who was using a Xerox word processor which was priced too high for grad students or for most offices. When I saw her correcting text, and cutting and pasting, my eyes bulged out like a Tex Avery wolf.

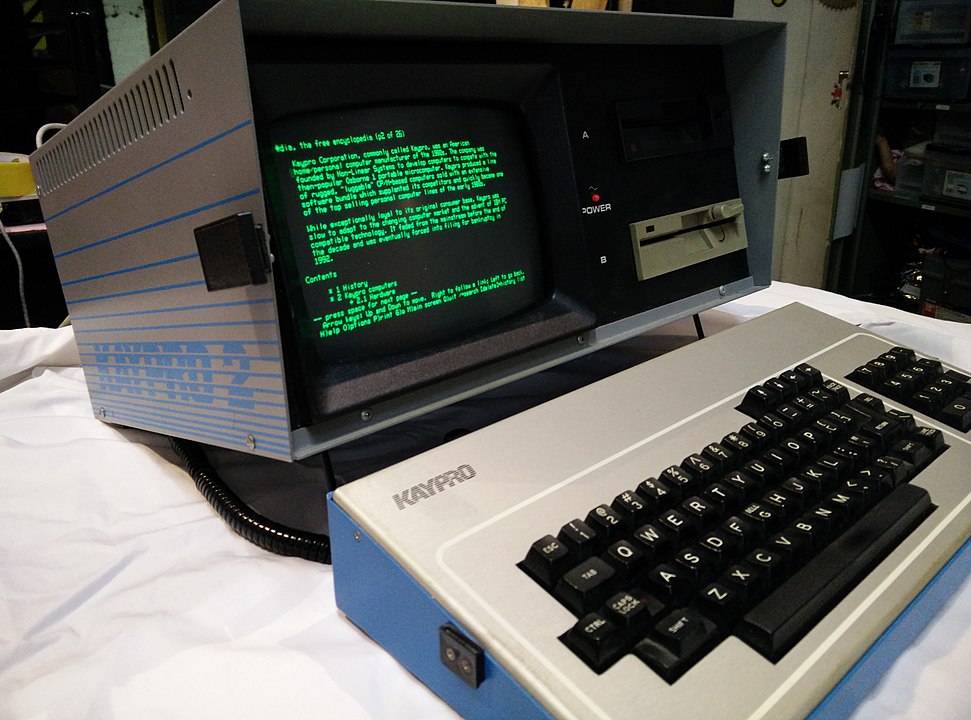

As soon as Kay-Pro II’s were available, I bought one from my cousin who had recently opened a computer store.

The moment I received it and turned it on, I got curious about how the characters made it to the screen, and became a writer about tech. In fact, I became a frequent contributor to the Pro-Files KayPro magazine, writing ‘splainers about the details of how these contraptions. worked.

I typed my wife’s dissertation on it — which was my justification for buying it — and the day when its power really hit her was when I used WordStar’s block move command to instantly swap sections 1 and 4 as her thesis advisor had suggested; she had unthinkingly assumed it meant I’d be retyping the entire chapter.

People noticed the deeper implications early on. E.g., Michael Heim, a fellow philosophy prof (which I had been, too), wrote a prescient book, Electric Language, in the early 1990s (I think) about the metaphysical implications of typing into an utterly malleable medium. David Levy wrote Scrolling Forward about the nature of documents in the Age of the PC. People like Frode Hegland are still writing about this and innovating in the text manipulation space.

A small observation I used to like to make around 1990 about the transformation that had already snuck into our culture: Before word processors, a document was a one of a kind piece of writing like a passport, a deed, or an historic map used by Napoleon; a document was tied to its material embodiment. Then the word processing folks needed a way to talk about anything you could write using bits, thus severing “documents” from their embodiment. Everything became a document as everything became a copy.

In any case, word processing profoundly changed not only how I write, but how I think, since I think by writing. Having a fluid medium lowers the cost of trying out ideas, but also makes it easy for me to change the structure of my thoughts, and since thinking is generally about connecting ideas, and those connections almost always assume a structure that changes their meaning — not just a linear scroll of one-liners — word processing is a crucial piece of “scaffolding” (in Clark and Chalmer‘s sense) for me and I suspect for most people.

In fact, I’ve come to recognize I am not a writer so much as a re-writer of my own words.

Figures

- Norsk Teknisk Museum – Teigen fotoatelier, CC BY-SA 4.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons - By Autopilot – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39098108

Categories: culture, libraries, media, personal, philosophy, tech dw

[…] In fact, I’ve come to recognize I am not a writer so much as a re-writer of my own words. —Joho the blog 2023-01-14 […]

[…] In fact, I’ve come to recognize I am not a writer so much as a re-writer of my own words. —Joho the blog 2023-01-14 […]

[…] In fact, I’ve come to recognize I am not a writer so much as a re-writer of my own words. —Joho the blog 2023-01-14 […]