August 30, 2015

Speaker info

August 27, 2015

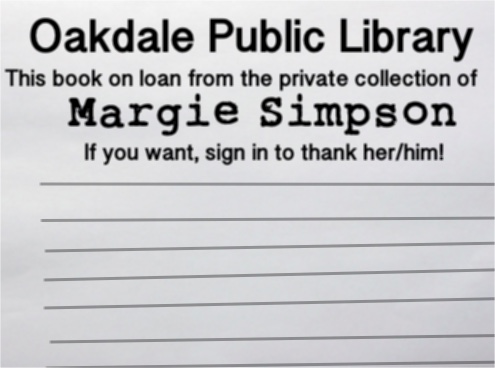

From the collection of…to your local library

Here’s a sticker I’d like to see inside a book sometime:

Let’s say you buy a paper version of a current best-selling book. You read it. You want to have it on your shelf, but you know you’re not going to re-read it for a while.

So, why not lend it to your local library? As the owner, you can reclaim it at any time, although maybe your library would prefer you lend it for a known term so that they can count on reducing the number of copies of a bestseller they have to buy. At the end of the loan period, it comes back to you, still warm from the hands of your neighbors .

And maybe the people in your community who read your book will sign the form as a way of thanking you.

Yes, this shouldn’t be confined to bestsellers. But that would help with the problem facing public libraries that the demand for recent books falls off sharply as the next bestsellers come along, leaving libraries with 99 more copies of 50 Shades of Gray than they need.

August 22, 2015

August 21, 2015

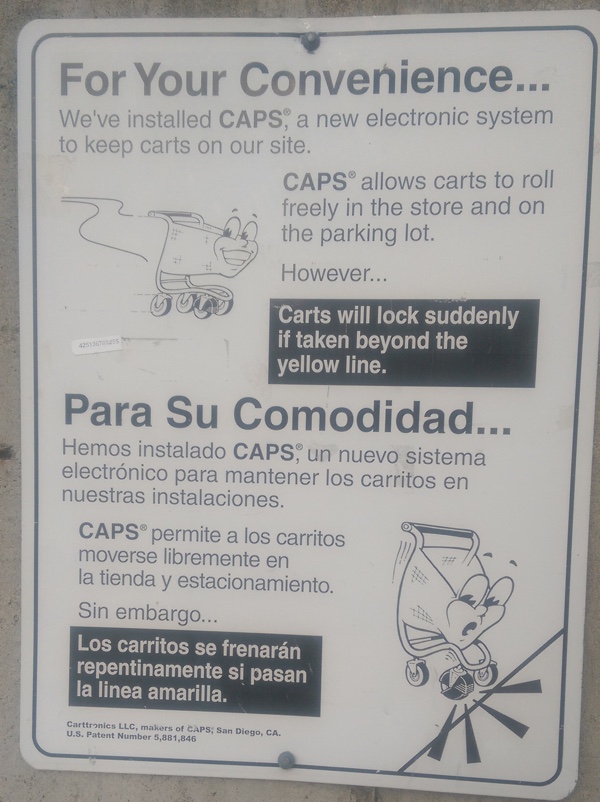

Morning puzzler

Here’s an uninteresting photo I took this morning:

Here’s my trick question:

Which way is up?

August 20, 2015

Remember when a drop didn’t matter?

I to the world am like a drop of water

That in the ocean seeks another drop…

—Comedy of Errors1, II:1:199-200

Shakespeare is bringing before us both the vastness of the ocean and the indistinguishability of one drop from another, and maybe even the way in which drops in an ocean are artificial constructs. But for us, “a drop in the ocean” is the standard signifier of an amount so small that it makes no difference at all. A drop in the bucket could still add up to something. A drop in the ocean could not.

You can see the power of this image in the startling effect its inversion had in Kurt Vonnegut‘s Ice Nine. A single drop of this fictitious chemical would crystalize the entire ocean. Imagine, a mere drop in the ocean having such an effect!

Of course, when it comes to racism, for a long time in this country (and only this country), having one drop of “Negro” blood in your veins — a black ancestor in any generation back to the presumed-white Adam and Eve — was enough to make you subject to all of the racial and social restrictions white America had devised. [More] Unlike an ocean drop or bucket drop, a blood drop could make all the difference. But, racism is all about being inconsistent, so maybe we shouldn’t be surprised.

When it came to tiny bits that didn’t matter at all, a drop in the ocean was the measure.

Not any more. All those drops have added up. Depending on where you’re floating, if you were to withdraw a drop from the ocean, there’s a measurable probability that you’ll come down with hepatitis. In some parts of the ocean, your dropper will get clogged with plastic. No drops for you.

We used to say that the ocean is forgiving. It turns out it was just nursing a grudge.

We have suffered from the Fallacy of Scale. We are now learning the power of drops. Perhaps too late.

1Speaking of Comedy of Errors, don’t miss the hilarious version at Shakespeare & Co. in Lenox, Mass. It’s set in NJ, and they play it entirely for laughs because, well, it’s a comedy.

August 18, 2015

Newton’s non-clockwork universe

The New Atlantis has just published five essays exploring “The Unknown Newton”. It is — bless its heart! — open access. Here’s the table of contents:

Rob Iliffe provides an overview of Newton’s religious thought, including his radically unorthodox theology.

William R. Newman examines the scientific ambitions in Newton’s alchemical labors, which are often written off as deviations from science.

Stephen D. Snobelen — who in the course of writing his essay discovered Newton’s personal, dog-eared copy of a book that had been lost — provides an in-depth look at the connection between Newton’s interpretation of biblical prophecy and his cosmological views.

Andrew Janiak explains how Newton reconciled the apparent tensions between the Bible and the new view of the world described by physics.

Finally, Sarah Dry describes the curious fate of Newton’s unpublished papers, showing what they mean for our understanding of the man and why they remained hidden for so long.

Stephen Snobelen’s article, “Cosmos and Apocalypse,” begins with a paper in the John Locke collection at the Bodelian: Newton’s hand-drawn timeline of the events in Revelations. Snobelen argues that we’ve read too much of The Enlightenment back into Newton.

In particular, the concept of the universe as a pure clockwork that forever operates according to mechanical laws comes from Laplace, not Newton, says Snobelen. He refers to David Kubrin’s 1967 paper “Newton and the Cyclical Cosmos“; it is not open access. (Sign up for free with Jstor and you get constrained access to its many riches.) Kubrin’s paper is a great piece of work. He makes the case — convincingly to an amateur like me — that Newton and many of his cohorts feared that a perfectly clockwork universe that did not need Divine intervention to operate would be seen as also not needing God to start up. Newton instead thought that without God’s intervention, the universe would wind down. He hypothesized that comets — newly discovered — were God’s way of refreshing the Universe.

The second half of the Kubrin article is about the extent to which Newton’s late cosmogeny was shaped by his Biblical commitments. Most of Snobelen’s article is about a discovery in 2004 of a new document that confirms this, and adds to it that God’s intervention heads the universe in a particular direction:

In sum, Newton’s universe winds down, but God also renews it and ensures that it is going somewhere. The analogy of the clockwork universe so often applied to Newton in popular science publications, some of them even written by scientists and scholars, turns out to be wholly unfitting for his biblically informed cosmology.

Snobelen attributes this to Newton’s recognition that the universe consists of forces all acting on one another at the same time:

Newton realized that universal gravity signaled the end of Kepler’s stable orbits along perfect ellipses. These regular geometric forms might work in theory and in a two-body system, but not in the real cosmos where many more bodies are involved.

To maintain the order represented by perfect ellipses required nudges and corrections that only a Deity could accomplish.

Snobelen points out that the idea of the universe as a clockwork was more Leibniz’s idea than Newton’s. Newton rejected it. Leibniz got God into the universe through a far odder idea than as the Pitcher of Comets: souls (“monads”) experience inhabiting a shared space in which causality obtains only because God coordinatis a string of experiences in perfect sync across all the monads.

“Newton’s so-called clockwork universe is hardly timeless, regular, and machine-like,” writes Snobelen. “[I]nstead, it acts more like an organism that is subject to ongoing growth, decay, and renewal.” I’m not sold on the “organism” metaphor based on Snobelen’s evidence, but that tiny point aside, this is a fascinating article.

August 17, 2015

Newton was not an astrologer

I got a little interested in the question of Isaac Newton’s connection to astrology because of something I’ve been working about casuality. After all, Newton pursued alchemical studies with great seriousness. And he gave us a theory of action at a distance that I thought might be taken as providing a rationale for astrological effects.

But, no. According to a post by Graham Bates:

In a library of 1763 books, (1752 different titles excluding duplicates) he had 369 books on what we would call scientific subjects, plus 169 on Alchemy (including many of the important texts on the subject copied in his own hand), there were also 477 books on Theology. He possessed only four books on astrology; two of these were treatises on astrology, one was an almanac, and one was a refutation of astrology

Bates says that a book on astrology that he purchased as a boy led him to learn about Euclid’s theorems so he could construct an astrologocial chart, but that is the extent of his known interest.

Bates also does a good job tracking down a spurious quote:

There is a story, much quoted in astrological articles and books, about a dispute between Newton and Halley (of the comet fame), supposedly about astrology, in which Newton replies to a remark by Halley “I have studied these things, you have not”.

The actual quote refers to theology, not astrology. So, no, Newton was not practitioner of astrology and there’s no reason to think that he gave it any credence. (Me neither, by the way.)

The post is on the Urania Trust site, which I had not heard of before. The group was founded in 1970 “to further the advancement of education by the teaching of the relationship between main’s [sic] knowledge of, beliefs about, the heavens and every aspect of his art science philosophy and religion.” Given its commitment to taking astrology seriously, the fairness of its post about Newton is admirable.

(Now if I could only find out if Newton played billiards.)

August 13, 2015

Back when tags were budding

I just came across an article from my old JOHO newsletter, from May 2005, that I wrote for Esther Dyson’s Reality 1.0. It was titled Trees and Tags— An Introduction, and it was about the limitations of taxonomies and the rise of tags. I must have been writing or researching Everything Is Miscellaneous at the time.

Here’s the introductory section. If you’re interested in ancient history, you can read the whole thing.

The Three Orders

The narrative that tells of the first man and woman encountering the tree of knowledge focuses on its tempting fruit. But after we took the bite, we apparently looked up and got the idea that knowledge is shaped like the tree’s branching structure: Big concepts contain smaller ones that contain smaller ones yet. Over the millennia, we have fashioned the structures of knowledge in just such tree-like ways, from the departmental organization of universities (liberal arts contains history and history contains ancient Chinese history) to the hierarchy of species. The idea that knowledge is shaped like a tree is perhaps our oldest knowledge about knowledge.

Now autumn has come to the forest of knowledge, thanks to the digital revolution. The leaves are falling and the trees are looking bare. We are discovering that traditional knowledge hierarchies that have served us so well are unnecessarily restricted when it comes to organizing information in the digital world. The principles of organization themselves are changing now that they are being freed from the constraints of the physical world. For example:

-

In the physical world, a fruit can hang from only one branch. In the digital world, objects can easily be classified in dozens or even hundreds of different categories.

-

In the real world, multiple people use any one tree. In the digital world, there can be a different tree for each person.

-

In the real world, the person who owns the information generally also owns and controls the tree that organizes that information. In the digital world, users can control the organization of information owned by others. (Exception to the rule: Westlaw owns the standard organization of case law even though the case law itself is in the public domain.)

These differences are so substantial that we can think of intellectual order as entering a third age. In the first, we organized the things themselves: We put books on shelves and silverware into drawers. In the second, we physically separated the metadata from the data: We built card catalogs and drew diagrams. In the third, the data and the metadata are digital, untying organization from the strictures of the physical world. In response, we are rapidly inventing new principles and tools of organization. When it comes to innovation on the Internet, metadata is becoming the new content.

But traditional taxonomic trees aren’t something we can throw away without a thought. They are an amazingly efficient way of organizing complexity because they enable us to focus on one aspect (e.g., that’s an apple) while keeping a universe of context (it’s a fruit, part of a plant, a type of living thing) in the background, ready for access. Tree structures are built into our institutions. They may even be built into our genes. So we are in a confusing and fertile period as we try to sort out what works and what doesn’t. Without trees, how would we organize college curricula, business org charts, the local library, and the order of species? How will we organize knowledge itself?

We may be on the path to finding out.

August 12, 2015

Did we sleep in caves all night?

When we slept in caves

did we ever sleep all night?

With the bears aware outside

And the snakes wound up tight?

With no blanket but your pal

And a pillow made of naught

It’s hard indeed to believe

any winks at all were caught.

But now we act as if

we’ve a right to sleep right through

the cries of tots and shouts and shots,

— if not, we’ll find someone to sue.

What’s natural is that we stayed up.

A good night’s sleep is all made up.

August 11, 2015

1M copyright free images ready for viewing and tagging

The British Library has posted one million public domain images — images not subject to any copyright restrictions — at Flickr. (They did this at least a year ago, but it’s still worth noting, isn’t it?)

The public can view them, copy them, and reuse them freely in every regard. An article in Quartz by Anne Quito reports:

So far, these images, which range from Restoration-era cartoons to colonial explorers’ early photographs, have been used on rugs, album covers, gift tags, a mapping project, and an art installation at the Burning Man festival in Nevada, among other things.

The Library posted them not only so they could be enjoyed and reused, but so the public would do what the Library is not staffed to do all by itself: add tags. Says Quartz:

to date, the collection has garnered over 267 million views, and over 400,000 tags have been added to images on Flickr by users. Through a “tagathon” with the Wikimedia UK community, the Library discovered over 50,000 maps in the collection, which they are now in the process of fitting into a modern map.

I can’t figure out how to search within a collection at Flickr, but this view at least does some clustering.