May 15, 2009

Speaker info

Footnoter

I frequently write in HTML, but find footnotes (endnotes, actually) a pain. I don’t like having to interrupt my flow to jump to the end of the document to plunk in a footnote, and I hate having to decide on a number not knowing if I might decide to insert a footnote ahead of the one I just inserted. So, primarily because I enjoy writing utilities for myself, I spent far more hours writing a tool that will make it easier for me than the tool itself will save.

Footnoter lets you embed footnotes in the middle of an HTM document. [[For example, this might be a footnote]] It looks for the designated delimiters, pulls the footnote out, puts it at the end, and leaves a hyperlinked number in its stead. It defaults to the quick-and-dirty HTML that uses <sup> to superscript the number, but the Advanced section lets you instead insert CSS classes for the marker in the text, the marker that precedes the footnote, and for the footnote itself.

Some warnings if you decide to try it out. First, It’s fragile. I’ve barely tested it. I’m sure there will be lots of ways it can be broken. (Nested footnotes won’t work.) Second, you would be a damned fool to paste its results over your only copy of the document you’ve been working on. Third, I am a baboonish, flatfooted writer of programs. What I write is the oppoosite of elegant: I prefer the long way of doing it and of writing it, since I can barely follow what I’m doing. Besides, the programs I write are so small and confined that efficiency doesn’t really matter.

If you care to try Footnoter out, with fear in your limbs and forgiveness in your heart, it’s here.

May 14, 2009

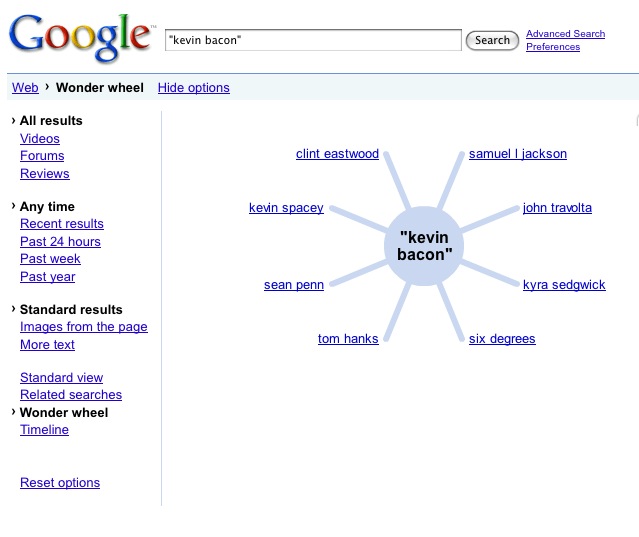

Google Wonderwheels

Let the games begin.

(Wonderwheels are a new browsing option available when doing a Google search. When you do a search, click on “Show Options” and then on “Wonderwheel.”)

May 13, 2009

TED translates

TED has started a great new project: Distributed translations of TED Talks. Taking a page from Global Voices, it’s crowd-sourcing translations.

This is exactly what should happen and is a great solution for relatively scarce resources such as TED talks. Figure out how to scale this and get yourself a Nobel prize.

By the way, TED has also introduced interactive transcripts: Click on a phrase in the transcript and the video skips to that spot. Very useful. And with a little specialized text editor, we could have the edit-video-by-editing-text app that I’ve been looking for.

Worst. Star Trek. Ever.

Thanks to the hilarious The Onion video on the new movie. Oh, what the heck, here it is:

Trekkies Bash New Star Trek Film As ‘Fun, Watchable’

May 12, 2009

[berkman] David Bollier on the commons

David Bollier is giving a Berkman talk on governing the commons. David is the author of Viral Spiral: How the Commoners Built a Digital Republic of Their Own. His talk: “How shall we govern the commons?”

|

NOTE: Live-blogging. Getting things wrong. Missing points. Omitting key information. Introducing artificial choppiness. Over-emphasizing small matters. Paraphrasing badly. Not running a spellpchecker. Mangling other people’s ideas and words. You are warned, people. |

His book looks at the arc of the development of open access and commonses. [What the heck is the plural of “commons”?] The commons is a new sector, and how we govern it is an urgent issue. Benkler, Zittrain, Lessig, and Bauers have addressed this, David says.

The commons is an ancient, new, and misunderstood paradigm, David says. It dates back to the medieval grazing of cattle. It’s a social system for managing shared resources. It was also a source of collective purposes, and custom and tradition. He recommends “The Magna Carta Manifesto” that looks at the struggle for the commons, with the Magna Carta being an armistice. The public domain was the closest we had to a commons until around 2000. The public domain was viewed by copyright traditionalists as a junkyward because the only people in it were things that had no commercial value. The first law review article on the commons didn’t occur until 1981. He cites Jack Valenti, a rich quote about a public domain work as “soiled and haggard, barren of its previous virtues.” Richard Stallman showed the efficacy and virtues of free software. He showed that incompatible code leads to a tower of Babel. The problem with Stallman’s Emacs Commune was that everything had to feed back to a central source (Stallman) and there was no governance. The General Public License gave legal protections to the Commons. Then the Net took off. We got new infrastructures for building commons, technologic, legal, and social.

Garrett Hardin who wrote about the “tragedy of the commons” later acknowledged that it didn’t apply to commons that have governance. The commons is generative (to use Jonathan Zittrain‘s term). “The commons is a macro-economic and cultural force in its own right.” So, how shall we govern it? “This area is terribly under-theorized.” Elinor Ostrom set forth 8 design principles to allow a commons to be governed as a commons, e.g., clear boundaries, appropriateness to the local area, monitoring, transparency, graduated sanctions against free riders and vandals…

Ostrom once showed David a photo of a chair occupying a shoveled out space during a snow storm with a chair occupying it until the person who shoveled it comes back. Ostrom says that that’s a commons because, “It’s a shared understanding by the neighborhood about how to allocate a scarce resource.” David says a commons arises when a neighborhood decides to manage a resource in an equitable way. One thing this shows is a conflict between commons governance and government, since the mayor tried to ban this practice.

He says we need a new taxonomy of digital commons. How do you protect the integrity of the shared resource and the community itself. He points to some distinctions:

Open vs. Free raises questions of business appropriation vs. community control, digital sharecropping vs. commons governance, monetization or maintenance as an inalienable resource.

Individual choice vs. Community. Creative Commons may undermine commons building because it allows opt in or opt out. The GPL is a purer type of commons: There’s a binary choice: you’re in the commons or you’re not.

Building within the house of copyright or challenge property discourse? Niva Elkin-Koren, for example, thinks CC encourages self-interest and doesn’t build out a coherent commons vision. [Paraphrase of a paraphrase! Reader beware!] The Global South views CC as depending on Western law and as a type of derivative of private property. Fair Use activists, on the other hand, want us to grapple wit hte prevailing practices in copyright law.

Commons vs. Markets. Or at they friends? It depends. There’s a spectrum. Open platforms. Innocentive (drug queries where answerers get a bounty). Democratizing innovation, a la Eric Von Hippel. Magnatune (a “respectful interface between the commons and the market”) or the Grateful Dead allowing home-made recordings. Market-oriented non-profits.

The commons is, David says, a “new social metabolism for governance and law, with economic and cultural impact.”

Q: How about more examples? How about Huffington Post?

A: Open platform with some participation. But how about: WikiTravel is an interesting mix. DailyKos: A user-generated community of commentary. Internet Archive. Flickr. Jamendo library of CC music. Blip.tv.

Q: (doc searls) You offer an organic metaphor, whereas we think of the Commons as a space. Will it take?

A: Who knows. But it presents it as a relationship.

Doc: I wonder if there’s a relato-sphere that isn’t metabolic. A metabolism burns energy. It creates gas.

A: A legal system is a conversation about shared power [he quotes someone I missed, and I’m paraphrasing] Q: But metabolism also implies homeostasis. A: Its organic property is why commons sometimes outperform markets. Charlie Nesson: Don’t confuse law in principle (we all live under the law, a set of shared values) and as a social environment (a mediated discourse in which people are assisted in relating by its structure).

Q: What about the international aspect of commons.

A: Cf. “Global Legal Pluralism.” There’s a case to dealing with this locally rather than doing it top-down through nation states. There are certainly tensions as you expand this trans-nationally.

Q: (wendy seltzer) The question of governance is partially a horiztonal dividing of what’s been shared and a vertical set of relationships to maintain the platform. Does this get towards how we can push for open platforms on which we can build commons?

A: Lessig once said he saw the amassing of a constituency for a commons as an important political strategy for assuring an open Internet. The commons is a verb, a commoning.

Q: The vast majority of free software projects are very hierarchical. The freedoms it lists are individualistic. Our rules on collective governance are based on highly individualistic control. How do we move forward.

A: The preponderance of SourceForge communities are small. How do you scale up governance? It is a key issue and I don’t know the answer.

Charlie: David Hoffman writes about this. It’s about creating a border that keeps out the griefers. That’s essential.

A: They have to be organically grow…

Q: [ethan zuckerman] The old idea of the commons was that we were independent homesteaders who can make our own butter. But the openness of the code doesn’t help most people. And it gets worse. A lot of the interesting communities are on closed, commercial platforms. The attempts to have a constitutional moment on Facebook are pathetic. How can you bring your thinking about governance into commercial spaces? Can that be done?

A: That’s the right direction. We have to find respectful relationships among private businesses and commons. Maybe we need new revenue models.

Q: [darius] The tragedy of the commons has devastated my country, Poland. Not because there was no governance. The structures were didn’t align public interest and private incentives. Intellectuals assumed people would contribute for free. You haven’t mentioned motivations…

A: Self-interest is far broader than traditional economists have regarded it. We need to devise structures that can be hearty and sustainable that serve the public interest.

Q: To what degree is power concentrated in different commons? Usually a small group holds veto power. E.g., most open source projects have lead developers. To what degree do you need a de facto leader?

A: You need de facto structures. And you do sometimes get concentrated monopolies where forking isn’t really an option.

Ben: Some large open source projects are governed democratically. E.g., Debian.

Q: [me]

A: I think you have a fragmented view. Trying to amass a unitary view of the commons is doomed to failure beause all of them have rootedness in the local

<

me: Do we need a meta rule that says here's how we maximize local control of commons?

A: That’s the direction we need to go in. But that’s a political frontier we haven’t gotten to.

[wendy seltzer] Is there a natural limit to the size of commons?

A: Maybe, but there are all sorts of technological prostheses…

wendy: When you tie this to communities…

A: There may be a type of speciation.

Q: Something like BitTorrent — a true commons where people are sharing resources — suggests that there’s an outside of the fence direction…

A: Commons has some way of integrity of its asset.

Q: Commons can fail. What are the most common failure modes?

A: Not having adequate enforcement of boundaries, etc. Part of what’s so fascinating is watching commons proliferate, and dealing with the theory later.

Q: [charlie nesson] I think of the commons as everything you can reach for free. There are forces that want to capture the potential of the commons. What we’re looking for is the engine that makes the commons itself robust enough to resist that. I think of the law as the instrument of enclosure. The root to building that robustness is not litigation. We have to build up a force. The question comes down not to how we govern the commons, but how do given enterprises build self-sustaining business models on a gift economy?

A: Yes. We’re trying to build our space, our own republic.

[I missed a bunch. Sorry. Check the Berkman webcast site to find the webcast.]

May 11, 2009

[berkman] Kenneth Crews on academic copyright

Harvard’s Office for Scholarly Communication has brought Kenneth Crews of Columbia Law School to talk about “Protecting Your Scholarship: Copyrights, Publication Agreements, and Open Access.”

|

NOTE: Live-blogging. Getting things wrong. Missing points. Omitting key information. Introducing artificial choppiness. Over-emphasizing small matters. Paraphrasing badly. Not running a spellpchecker. Mangling other people’s ideas and words. You are warned, people. |

How do all the things mentioned in his subtitle fit together, he asks, assuring us that they do.

Our goals as academics, he says, are to: advance scholarship, promote access to pubs, preserve academic freedom, expand the class roomk support research worldwide, build the next generation of research, and reduce the costs and barriers. Does it shift costs or reduce them, he asks?

Peter Suber defines open access as online, free of charage, and free of most copyright and licensing restrictions. Is that the right definition, he asks. He says that as he’s traveled around the world, he’s seen access to the Internet is expanding rapidly. “People are connected.” It’s there as a potential and is in place in many places. But, in many of these places, there’s no cash to buy access to content. They can get to content if it’s made available on line. So, in addition to those other goals he’s listed, there’s altruism.

Why right now? The Harvard resolution (2008) requiring open access. The NIH public access policy (2008) puts works PubMedCentral. There are, of course, pitfalls: Misuse of work, etc. [missed some. sorry.]

There are challenges to these policies now. Congress has a bill to undo the NIH open access policy. There’s the DMCA’s anticircumvention provisions; the Copyright Office is holding hearings right now about exemptions to those processions. There’s the Google Books settlement that would provide tight controls to the accessibility and usability of that content. “Are we putting together a database of 20M volumes that is guaranteed to frustrate the heck out of the users?” There’s our distaste of other people making money with other people’s copyrights.

He gives a quick review of copyright: Just about everything is protected, if it’s “fixed in some tangible medium.” Copyright is as set of rights wrt reproduction, distribution, derivatives, performane and display, and DMCA rights. These rights can be unbundled and parceled out by the rights holder. Who owns the copyright isn’t very important. The real question is who has the particular rights within that bundle

Those rights are transferable. But they may be transfered or licensed, exclusive or not. In scholarly publishing, I might transfer rights to a publisher who then licenses back to me certain rights, such as the right to use it in further research, or to post portions on my Web site. Or, I might not transfer any rights, and instead license some rights to my publisher. Maybe I’ll license it to the publisher, stipulating that it be Creative Commons licensed. There are many, many possibilities. “So the process of engaging with a publisher is …. a process of negotiation.”

The context is changing. It’s becoming digital. Digital tech both can make scholarship more easily available, and it holds the potential for controlling access. Open access is key to the growth of scholarship. “The growth of scholarship comes from access to existing works,” as does its impact.

So, being a good steward of copyright requires understanding our interests, those of our institution, the revenue possibilities, and the interests of people I do not know and who may not be in my field. We should worry about maintaining the integrity of our work. Money matters. We need to worry about the business models.

“Not all copyrights are created equal…Not all works need to be treated in the same way.”

Who gets to decide all this: The author.

“Managing this work in a way that moves us toward open access publishing … is a good thing.” How to do that: Self publish. Use OA publishers (e.g., www.doaj.org). Put it in an institutional repository. And negotiate. “The happier the agreement, the longer the agreement.” “We have to look for language that does happy things for us.” He shows an example of happy language that gives the author right to post an article for free. Another: Language that lets the author use the article for her own work. A license leaves the unstated rights with the author. He notes that the law’s default does not require the publisher to include the author’s name and affiliation.

Tough questions about open access: Will colleagues respect publications in OA journals? (More so every day, he says.) OA compatible with peer review? (Yes, Kenneth says.) How do I manage my copyrights? How do I negotiate agreements? Who pays the pub costs. What about the economic surival of journals? (I don’t know the answers, he says, but the problem is more real than we often like to acknowledge.)

Key points of the talk, he says: . You have choices. Be a good steward. Negotiate…and keep a copy of the agreement. In fact, keep the agreement for the entire term of the copyright, i.e., 70 years after you’re dead.

Q: Google Books settlement?

A: Read the agreement. “It will really wow you.” The key point: It permits Google to continue scanning, and to create this “fantastically large, very useful archive of materials.” But access to it will be restricted. If a book’s in copyright, you can only get bibliographic info. If you want more, you sign up for a subscription. Tightly controlled, limited access. “And it’s a book selling situation.” Google and the association become major booksellers. You buy access, not copies. “The challenge for all of us is there is no question, this proposal should it become the legal standard, is the biggest, most important step toward digital access of materials not previous available.” We need to decide if we want to move into the future on these terms. “I only give this agreement several years before it falls apart” and they’re back in court looking for new terms.

Q: Robert Darnton: What kind of legislation should we have for orphan works [= works under copyright whose license holders cannot be found]

A: The Copyright Office’s legislative proposal from a few years ago was actually pretty good. But as it went through the process, “every change was a step backward.” “I thought it was a good thing the legislation died last year.” We’re in pretty good shape now with the Fair Use laws. The Google settlement allows the Registry to collect revenues from the use of works and distribute money out to the rights holders. But with an orphaned works, who gets it? The basic idea is that that money is used to pay organizational overhead. If there’s leftover money, 70% gets distributed to the class of known copyright holders. The other 30% goes into a pool for non-profits. “The serious problem is that it gives Google a monumental head start over anyone else in working with orphan works.” Competitors don’t have a court settlement that protects them from law suits over rights abuses. “This is a formidable problem with the agreement.”

Q: I edit an undergraduate Harvard journal. Authors sign over all rights to the journal. I worry about students being chagrined by their very first publication. Can an author ever get them back under wraps?

A: If I make something open access, can I reel it in if I change my mind? Legally, yes. Realistically, no. It’s probably been downloaded, mirrored, put into the Internet Archive.

Q: What about students’ lecture notes, etc.?

A: If everything created in a fixed medium is copyrighted, we have a responsibility to manage it. If you’re a student who created notes or papers, they’re yours. But, when it comes to wikis, etc., the copyright situation is nightmarish. It’s jointly copyrighted and owned. Any one student can exert rights.

Q: Every change in the copyright law has gotten awa from the original intent, which was to preserve creativity. The change to make everything copyrighted is nightmarish. Why not have a registry of copyright and require some action on the part of creators to get and renew a copyright?

A: So many ways I could respond! The US Constitution lists powers the Congress has. Most of those statements are very clear and simple. Then comes copyright: To promote progress in the sciences and useful arts, Congress has the power to granted limited-time rights to publish. It’s clear this has a purpose, a goal. There are many reasons we’ve gotten away from this. In addition to everthing else, the Berne Convention, which we joined in 1989, sets basic rules, including broad copyright with no formalities to get one. We couldn’t require registration to get a copyright without dropping out of Berne, but we’re locked into international provisions in multiple other agreements. You want change, go to Berne.

Smart and secure grids and militaries

The Wired.com piece I wrote about Robin Chase prompted Andrew Bochman to send me an email. Andy is an MIT and DC energy tech guy (and, it turns out, a neighbor) who writes two blogs: The Smart Grid Security Blog and the DoD Energy Blog. Neither of these topics would make it into my extended profile under “Interests,” but I found myself sucked into them (confirming my rule of thumb that everything is interesting if look at in sufficient detail). So many things in the world to care about!

May 10, 2009

Copyright debate at The Economist

Economist.com is featuring a debate on whether current copyright laws do more harm than good. The “Yes, they do” side is represented by Terry Fisher, a faculty director of the Berkman Center. The “No, they don’t” position is argued by Justin Hughes. Excellent discussion.

Comedy night at the White House

Obama’s comedy routine at the White house Corrrespondents’ Dinner was both funnier and edgier than I would have expected. Oh, some jokes were pure Johnny Carson, (“How about that Joe Biden? I wouldn’t say he’s talkative, but he’s personally responsible for the Amtrak Quiet Car now having armed conductors. Heyo!”), but some had real bite. Fun.

Wanda Sykes was funny, too, although she did go over the line a couple of times, imo. The Limbaugh jokes in particular were just mean. But I’d rather have the institutionalized dinner go over the line than say so far below it. (See here, starting 2 minutes in. And watch the audience cutaways.)

The whole ritual is as close as we get to giving our president a court jester to keep him humble. But the expectation that the president is going to do stand-up, well, it’s a tad bizarre. And I like it.