Linnaeus’ paper

The Linnean Society‘s entrance is tucked away in plain sight, just another stone portico and another dark oak door, across from the Royal Geological Society, and sharing a courtyard with the far larger Royal Academy of Arts. Inside, the headquarters is done in mustard and parchment white, with wood trim and brass, all very British and 19th Century.

Go up a flight of portrait-lined stairs and you are in the two-story library decorated with prints of carefully drawn specimens (flowers, worms, ticks, “Syncorme pulchella”), portraits of people important in the Society’s history, and a three-foot-high statue of the man himself, at the base of which someone has laid ornamental squash and drying flowers.

Tucked away near the entrance is a 12-drawer card catalog of the library’s books arranged by author. In the work room across the hall sits a computer that allows you to search by abstract, key words, notes, titles, and subjects. There is no hierarchical topic listing.

I wander back to the first floor and pull back the cloth on a couple of glass-topped tables that exhibit some of Linnaeus’ original specimens, the reference points for disputes about whether a particular binomial — the genus-species names Linnaeus pioneered — refers to this or that creature. If you want to be sure, you can look at the remains of the being Linnaeus held in his hand when he said “I name thee…thus!”, the very moment represented in his triumphal statue outside the courtyard, part of the Royal Academy. To the statue’s right are Cuvier and Leibniz. Above him and to his left stand Newton, Bentham, Milton and Harvey. Static hierarchies force tough choices.

When Mike Olmert’s undergraduates from the University of Maryland arrive, Gina Douglas, Librarian and Archivist, takes us all into the Meeting Room. There, on extraordinarily uncomfortable benches — I feel like a cry baby when one of the brochures brags about the modern padding — we listen to Ms. Douglas explain that Linnaeus’ collection ended up in London because his widow sold it for dowery money for her daughters. The buyer was a rich young British scientist eager to make his mark. It worked, as the prominence of his oil portrait proves.

Linneaus, she tells us, knew his classification system was artificial and looked forward to the day when it would be replaced by the “real” one. (Without a theory of animals descending from other animals, it’s hard to imagine what would make one set of morphological likeness more real than another. I should re-read Foucault.)

Ms. Douglas divides the group in two and takes the first half down one flight to the collection room, a room protected by a 6-inch thick metal door and designed to survive a nuclear bomb. “The whole of the taxonomic world depends on the legal concept of the type,” she explains. The brochure says: “The Linnaean Collection comprises the specimens of plants (14,000), fish (158), shells (1,564) and insects (3,198) acquired from the widow of Carl Linnaeus in 1784 by James Edward Smith.” It doesn’t seem possible that this room contains all those specimens, plus all of Linnaeus’ own book collection.

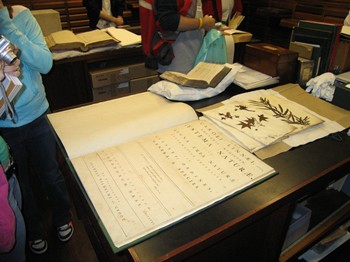

The room is about 15 feet square, lined with specimen drawers and book shelves. Ms. Douglas opens an oversized book, a first edition of Linnaeus’ classification system. There he has named and organized God’s creatures so that we can have a common way to talk about them. She turns the pages: Animals, vegetables, minerals…so common to us now that they have almost become a nursery rhyme. In this book they are new.

She draws our attention to the two page spread devoted to the Animal Kingdom. On the extreme right is the category “Vermes” (worms) which Linnaeus used as a catchall. If it wasn’t an insect, he put it into the Worms, as close as Linnaeus came to having a “Misc.” category.

Ms. Douglas spreads out some specimen pages, each with one plant type, gray as dust, attached. “Notice the K on that one,” she says, pointing to a small letter at the bottom of the page. “That tells us who collected it. It’s rare for a page to have that information.” Too bad because some of the specimens I saw in the cases upstairs had been misidentified: Linnaeus grew Solanum quecifolium from seeds that he thought were from Peru but were actually from somewhere near Mongolia. If only he had had better metadata to work with…

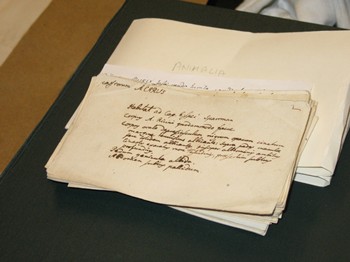

Ms. Douglas takes out a thin pile of 3×5 cards, as soft as handkerchiefs. On each, Linnaeus has recorded in his fine hand one classified species.

This moment, as close as I’ll ever get to seeing Linnaeus at work, makes clear how the requirements of the physical world silently persuade us to shape our understanding: Linnaeus’ classification resulted from the nature of paper. Because you only have one card for each species, your order will give each species one and only one place. You will organize them by putting cards near cards like them, naturally producing an ordered series or a set of clusters. As you lay out your cards, like next to like, you are drawing a map of knowledge. That’s why Systema Naturae is oversized: a map makes the most sense when you can see it all at once. (The size of the paper also determines the degree of detail possible on the map.) The largest units in Linnaeus’ classification are kingdoms not because Animals, Vegetables and Minerals somehow lord it over the particular creatures they contain, but because kingdoms are the most inclusive territories on political maps. Knowledge thus derives its nature from the paper that expresses it: Bounded, unchanging, the same for all, two-dimensional and thus difficult to represent exceptions and complex overlaps, and all laid out in a glance with no dark corners.

Our time is up. The next half of the group waits quietly for us to ascend the narrow stairway. [Technorati tags: EverythingIsMiscellaneous taxonomy linnaeus]

Categories: Uncategorized dw