May 2 . 2005

ContentsWhy I'm a pessoptimist —The Right to Connect:

Let's not be too quick to compromise. |

| It's a JOHO World After All The big news for me is that, after 1.5 years of work, I've sent my book proposal out to publishers. It's called Everything Is Miscellaneous. It'll take 2-3 weeks to find out if any want to publish it. A few have expressed interest — good, but interest is cheap — to my agent. Fingers crossed. (Of course, if a publisher accepts it, I'll have to actually write the book. Hmm, I hadn't thought of that...) In other news, I did a couple of "What's New in the Blogs?" segments for MSNBC, but it didn't work out. And I've been on the road way too much, mainly talking about the topic of my potential, putative, hypothetical book. Also, my fellowship at the Harvard Berkman Center has been renewed for a year. Yay! |

Why I'm a pessoptimist —The Right to Connect

David Isenberg's Freedom to Connect conference last month brought together a bunch of telco rebels and cultural observers for two days of talk about how we can keep the world of Big Control from slamming the window shut on us. I gave the wrap-up keynote. Unsure what to say, I blurted for a continuous 20 minutes. This is something like what I said:

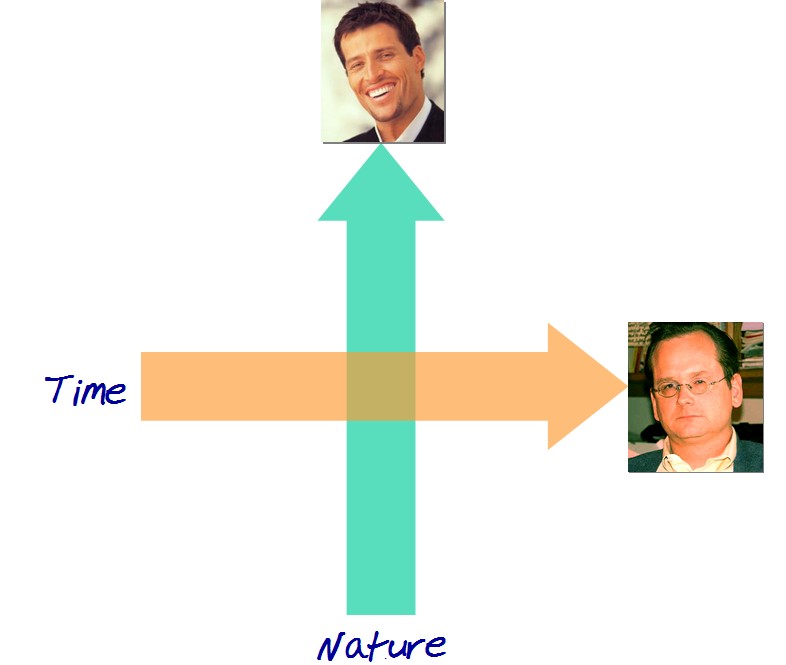

I'm confused. On the one hand, I'm a raving Tony Robbins optimist. On the other hand, I'm a Lessigian pessimist. The other day I figured out how I can contain such a contradiction. It's very simple.

In terms of human nature, I'm sunny. I think we're fundamentally good. More exactly, we humans are fundamentally social, and sociality is the source of goodness. Obviously we do bad things and our circles of sympathy are never wide enough —some sociopaths can't get past their own fingertips —but basically we care about one another.

In terms of the unfolding of time, I'm pessimistic. I think we're going to lose the important battles over the Internet and there are going to be strong controls over "private" use. The forces arrayed against us are monumental

So, I want to invigorate Isenberg's phrase and say that the freeom to connect is based on a right to connect. There's a big difference. Freedoms are granted. Rights are things we can demand. And we need to be demanding them in public places at the top of our lungs.

Rights and duties traditionally go together: if I have a right, then there's someone I can demand it of. That isn't how it was initially, in our culture, though, because God and kings had rights and the rest of us only saw the duty end of the stick. But eventually we came up with the idea that we the people were endowed with rights simply because we're we the people: life, liberty, property, even the pursuit of happiness. And in 1948, the world, via the United Nations, decided that maybe education, healthcare and education might be services we have the right to demand from our governments: Freedom of speech doesn't mean too much if flies are climbing in and out of your kids' mouths.

Beneath the architecture of rights, though, is our insane, pervasive, ubiquitous sociality. Rights only make sense within a social context, unless you're Job arguing with God, and even then the fairness he was demanding had to do with his place in the social fabric. We have rights only because we are connected.

But what is this connection? You know what it is. But let me point to three elements:

We're aware of others.

We care about those others.

We can see what they see.

Obviously, not all connection is good. People are using the Net to coordinate horrific attacks. Of course. But connection is an a priori good, something that one needs a special reason to refuse but not a special reason to grant. Connection should be the default. And given how important connection is to what it means to be human —not to mention that it underlies the accepted human rights —connection should be a right, something we can demand.

The Japanese blogger and international man of goodness, Joi Ito, blogged on March 24 about a conference he was at in India:

Later, an elderly man stood up and said that all knowledge should be available to everyone and that he didn't think we should compromise on the copyright issues. He then said that the people are ready to fight and march in the streets and turn over the monopolies and we didn't need to sit around and wait for government. It turns out he used to live with Mahatma Gandhi's at his Ashram.

I'm not saying that man has the tactics down. But he's right that it's a good time to state what we believe. So, here are three truths that I think are (sort of) self-evident:

1. Free music is awesome. That doesn't mean all file-sharing is ok or artists should work for free. Not at all. But in the debate over the new business model, we should remember that having access to the world's music is an unimaginable boon that should weigh heavily in the balance.

2. Rules are the exception. We resort to rules when everything fails. More often, we manage to live together by granting each other leeway, through forgiveness, by having a sense of humor. We should be careful not to construct our new world by starting with rules, even if the rules are fair.

3. Anonymity is liberating. Sure, bad people do bad things under the cloak of anonymity. But anonymity also lets dissidents escape some of the strictures of their governments and let us all explore areas —from health information to porn —we do not want others to know we care about. Anonymity isn't only, or even primarily, for the guilty.

We need to speak plainly because conditions are too dire to mute our opinions. Of course we can and will compromise, but we should not start from compromised positions.

We need to fight the enemies of connection. If connection is a matter of awareness, caring, and seeing, its enemies are ignorance, selfishness and the lack of imagination. And the remedies for those are education, emotion and art. Let's not be shy about this. (Also, it'd be good to win a freaking election already.)

We need to stand firm because: There is no freedom without connection. There is no peace without connection. There is no joy without connection.

Thank you and drive carefully.

Ethan Zuckerman and Rebecca MacKinnon, my Berkman buddies, have started a site that is turning out to be a crucial daily read for me. Called Global Voices, it aims at getting voices from around the world heard. The daily GV summary is indispensible.

Middle World Resources |

|

| Walking

the Walk

My goodness but the BBC is up to lots of interesting things! I don't even know where to start. Every episode of every program is getting its own URL and will be intensely metadated. An experiment lets you phone in to bookmark songs you hear on the radio. They're putting RSS all over the place. They're handing out video cameras to people who can't afford them and posting the results. The BBC is showing us what mainstream media might be like if its mandate were simply to make our lives better. |

Cool

Tool I'm not smart enough to figure out how to send a multi-page fax by scanning in paper using Windows XP's fax function. I can send them one at a time, but I don't really want to make a separate call for each page. There's got to be a better way! There is. It's called MightyFax —be sure to pick up the multi-page fax scanner attachment —and it'll cost you $20. It's not elegant, but it works.

|

|

I just finished Half Life 2, the greatest video game in history. At least in its genre. The graphics are not only technically astounding, they're well-drawn. The characters are all stock but pretty well acted, which puts it above most Bruce Willis movies. The physics are phenomenal; in fact, I wish someone would use it to create a physics simulator for students to play with. But what makes it so much fun is that it's consistently imaginative and inventive. It is more fun than the type of movie it emulates. Those lines have crossed. |

|

Everything Bad is very very good

I just finished Steve Johnson's new book, Everything Bad is Good for You. It's going to be a best-seller if there's any justice in the world. [Hint: There isn't.]

I've been reading Steve's stuff for some time now and I think I've discovered what makes his writing style so good: He thinks well. He turns corners and pulls you with him. It's the kind of unexpected unfolding that makes narratives work, but Steve does it purely in the realm of ideas. He writes so well because he's so damn smart. (Also, he just writes so damn well.)

This short new book has a strong and simple premise: Pop culture is making us smarter. The bulk of the book argues that pop culture is more complex than it used to be and more than we usually give it credit for. Look past the content of video games and TV, Steve says, and you'll see that their structures are far more complicated and demanding than ever before. (Deadwood should be his new favorite example.) He graphs the complexity of social relationships in Dynasty and 24, for example, and shows that the former is like a family while the latter is like a village. In following 24, we get better at understanding complex social relationships. He compares Hill Street Blues, the first mainstream multi-storyline prime-time show, with Starsky and Hutch before it and The Sopranos after it. There is no doubt: We've gotten far better at parsing interwoven plot lines and making sense of plots that aren't laid out for us like mackerels. Likewise, video games, he says, have gotten a bad rap because of their content, while once again their structure has been ignored. They teach us how to make decisions in complex environments, he says. Steve's quite wonderful at analyzing precisely the ways in which games, tv shows, and, to a lesser degree, movies demand more from us than before — his examples of "multiple threading, flashing arrows, and social networks," for example, are so insightful that they're funny..

There's no doubt in my mind that Steve is right that pop culture is more complex than before. But does that complexity make us smarter? Here he gets more speculative, suggesting that the rise in the average IQ might well be correlated with the way our culture is training us to be more actively intelligent. The causality is hard to prove, and Steve proceeds properly tentatively. We certainly have gotten smarter at following entertainments. Does that mean that we've gotten smarter outside of watching TV and playing video games? Or are we only better at following the new rules of TV narrative and video play? Common sense and intuition make me think that Steve is right: The complexifying of pop culture is making us smarter. But then I look at the election results and wonder. We seem more impatient with nuance than ever before in the political realm. Is pop culture training us to be smarter about anything except pop culture?

So, if it's a persuasive essay, am I persuaded?

1. That pop culture is getting more complex and requires more involvement to understand? 100%.

2. That this is making us smarter outside of pop culture? I lean that way but I'm not 100% convinced. Steve acknowledges the difficulty of proving either the fact or the causality.

3. That we should be more positive about pop culture? Definitely. Even so, I think Steve occasionally underplays the value of the old media that competes for our time. Although he's careful to say that he is not claiming books have less value than games and TV, I think for rhetorical purposes he doesn't give books their due. Despite an hilarious few pages about how books would look if video games had come first, books do something that video games, TV, theater and films don't do very well: Show us the world as it appears to someone else. Those media let us view how people different from us act in the world as it appears to them, but only in books do we actually live in that world. This, as Richard Rorty has pointed out, has moral value. Steve refers to this quality of books briefly at the end, but it struck me as ass-covering. And he he misses the opportunity to talk about it while developing his argument. For example, in Part One he writes:

Most video games take place in worlds that are deliberately fanciful in nature, and even the most realistic games can't compare to the vivid, detailed illusion of reality that novels or movies concoct for us. But our lives are not stories, at least in the present tense - we don't passively consume a narrative thread....Traditional narratives have much to teach us, of course: they can enhance our powers of communication, and our insight into the human psyche. But if you were designing a cultural form explicitly to train the cognitive muscles of the brain..." (p. 58 of the non-final bound galleys)

To my mind, that underplays the value of books and narratives. Great novels reveal a world; calling that an "illusion" denigrates their ability to show the truth.

And, to my way of thinking, the most important lesson of narratives isn't that they give insight into our psyches or teach us how to communicate. Instead, narratives show us that events unfold: The end was contained in the beginning but not in a way that we could have predicted. Narrative is about ambiguity and emergence, as Steve, the Brown-educated, lit-crit scholar and author of Emergence - buy it today! - knows. Had he kept that aspect of books in mind during the section on video games, for example, his point about the complex hierarchy of aims in the game Zelda would have been less convincing. Sure, we make decisions in games based on a nested stack of goals, and we learn the rules of the virtual worlds we're exploring. But those goals and rules are ultimately knowable and completely expressible. Although Half Life 2 is, as Steve points out, far more complex than the previous generation's Pac-Man, for all its amazing physics and integrated puzzles and pretty good pixelated acting, HL2 gives us a toy world. The world of Emma Bovary, on the other hand, doesn't resolve to rules and puzzles. It's messy, ambiguous, and truly complex. Of course Steve knows this, but he underplays it when pointing out the hidden complexity of video games.

Steve is not asking us to decide between books and contemporary pop culture. He obviously loves books. He defends pop culture by pointing out values in its structure that we've missed as we've focused on its often-offensive content. And this he does brillliantly. And entertainingly. This book is so much fun to read. All I'm saying is that in making his case, he undervalues one aspect of the old culture, which might otherwise have taken just a couple of lumens off the buff-job he's done on the new one.

But let me be unambiguous in my recommendation: Read this book. It will change the way you view pop culture. And you will enjoy every page and every surprising turn of thought.

Steve this morning replied to some of his reviewers, including me. I've replied to his reply here.

Disclosure: The book comes out May 5. Steve sent me bound galleys because we bonded at a conference last year. I was a major fan of his well before that.

Editorial Lint

JOHO is a free, independent newsletter written and produced by David Weinberger. If you write him with corrections or criticisms, it will probably turn out to have been your fault.

To unsubscribe, send an email to [email protected] with "unsubscribe" in the subject line. If you have more than one email address, you must send the unsubscribe request from the email address you want unsubscribed. In case of difficulty, let me know: [email protected]

There's more information about subscribing, changing your address, etc., at www.hyperorg.com/forms/adminhome.html. In case of confusion, you can always send mail to me at [email protected]. There is no need for harshness or recriminations. Sometimes things just don't work out between people. .

Dr. Weinberger is represented by a fiercely aggressive legal team who responds to any provocation with massive litigatory procedures. This notice constitutes fair warning.

Any email sent to JOHO may be published in JOHO and snarkily commented on unless the email explicitly states that it's not for publication.

.

The Journal of the Hyperlinked Organization is a publication of Evident Marketing, Inc. "The Hyperlinked Organization" is trademarked by Open Text Corp. For information about trademarks owned by Evident Marketing, Inc., please see our Preemptive Trademarks™™ page at http://www.hyperorg.com/misc/trademarks.html

This work is licensed under a Creative

Commons License.