Your First API Program

Library Innovation Lab's LibraryCloud Version

David Weinberger, July 6, 2014

The finished files for this project are available at:

http://hyperorg.com/misc/myFirstApiScript/myFirstApiScript.zip

| Contents 0. Introduction 0.1

Who this is for 1. The

HTML0.2 What we're going to do 0.3 How this will work 0.4 Wait, what are those things? 2. The JavaScript 2.1

AJAX and jQuery 3. PHP4. Displaying the results :Part 1 5. Putting it all together 6. Debugging 7. Making it better 7.1

Prettying it up 8. Beyond

LibraryCloud7.2. Extract more information 7.3 When you have questions 7.4 Share your code |

Section 0: Introduction

0.1. Who this is for

If you were attracted to this post by the phrase "API" rather than being scared off by it, this may be for you.

I'm going to take you through the basics of writing a program that accesses information on a site owned by some organization that has decided to make that information available through an API .

The data will come from Harvard Library, through the API provided by LibraryCloud.

The user interface will be the world's ugliest Web page.

To follow this tutorial, it's preferable that you:

- Have written a program before, so that you understand things like what a variable is

- Have a basic understanding of HTML

To do the examples, you should have installed on your computer:

- A text editor such as TextWrangler on the Mac or NotePad++ on a PC, although any plain old text editor will do. (If you like 'em, support 'em.)

- A Web server. On the Mac or PC, I'd suggest you install the free version of MAMP, which isn't hard but isn't easy. Alternatively, you could post the HTML files you'll be writing onto a hosted site, but I find running the web server locally (that is, on my own laptop) to be more convenient.

- The ability to run PHP scripts. That's included in MAMP and in most hosted sites.

- The free jQuery library.

I'll give you some help installing MAMP and downloading jQuery. All in good time.

0.2. What we're going to do

We're going to write a very simple Web page that lets a user type in a search term that will fetch information about books in Harvard Library's collection of thirteen million items that match that term. We'll be doing a basic "keyword" search that will look for the search term in many different parts of each item's record. So, a search for "London" will turn up London Travel Guide, Wild Thing by Jack London, and any Sherlock Holmes book that has "London" in its description.

0.3 How this will work

-

We'll write a Web page in HTML that presents the user with a place to type in a search term.

-

A "search" button will invoke a program written in JavaScript that will call a program written in PHP.

-

The PHP will interact with the the LibraryCloud API.

-

The LibraryCloud API will interpret the PHP program's request, and will come back with information about the books in the Harvard Library collection.

-

The PHP program will send that information back to the JavaScript.

-

The JavaScript will insert that information into the HTML as a list of titles.

0.4 Wait, what are those things???

HTML is the language that Web pages are written in.

JavaScript is a programming language that knows how to work with HTML. The browser on the user's computer that is displaying the HTML runs the JavaScript.

PHP is a programming language that runs on the web server that is serving up the HTML page the user is interacting with.

An API is an Application Programming Interface. It lets software applications request information from a site.

LibraryCloud is a server created by the Harvard Library Innovation Lab to make information about Harvard Library's collection of items accessible through an API. There's more about LibraryCloud here. Also, note that we will be interacting with the version of LibraryCloud created by the Harvard Library Innovation Lab. Another version is being constructed intended to be less experimental and more suitable as a part of the Library's official infrastructure.

Section 1: The HTML

HTML consists of content and markup. The content is what the user sees. The markup are instructions to the browser about how to format that content and how to make the content interactive.

The most basic Web page starts off with a header that the user doesn't see. The body has content the user sees and markup that's hidden from the user.

Here's the page we'll construct.

| 1 | <html> |

| 2 | <head> |

| 3 | <title>My first API script</title> |

| 4 | </head> |

| 5 | <body> |

| 6 | <H1>Searching Harvard Library</h1> |

| 7 | <p>This page lets you search Harvard Library's collection.</p> |

| 8 | <textarea id="searchbox"></textarea> |

| 9 | <input type="button" value="Search!" onclick="doSearch()"> |

| 10 | <div id="resultsdiv"></div> |

| 11 | </body> |

| 12 | </html> |

Open up a new file with your text editor and paste this in. Save it in a new folder (maybe call it "MyFirstApiScript" and maybe call this file "MyFirstApiScript.html" somewhere on your computer. Note: click on the "Toggle line numbers" button so that you can select and copy just the text.

Let's go through it line by line.

1. <html>

Elements that are within angle brackets (< >) are markup, or "tags." The first piece of markup tells the browser that this is an HTML document. Note that the very last line repeats the "html" tag but puts a forward slash before it ("</html>"); this tells the browser that we are now at the end of the HTML document. Most HTML tags follow this convention of repeating the tag with a / to flag that the tag is no longer in effect.

2. <head>

This tag tells the browser that everything up through the </head> tag on line 4 is to be considered an invisible instruction.

3. <title>My first API script</title>

This tells the browser what name to display in its title bar or tab.

5. <body>

This tells the browser that the visible part of the page begins here.

6. <H1>Searching Harvard Library</h1>

<H1> is a standard HTML tag that tells the browser to format the content as if it were a first level (i.e., major) heading.

7. <p>This page lets you search Harvard Library's collection.</p>

Likewise for <p>, a tag used for "normal" paragraph text.

8. <textarea id="searchbox"></textarea>

A textarea is a built-in HTML object that provides a space that the user can type into (like this: . In this case, we've added a little more invisible information to the textarea: we've given it an ID of "searchbox." We could have used any combination of letters and numbers (although there are some rules forbidding weirdnesses). The JavaScript we'll write will use that ID to get information out of the textarea.

9. <input type="button" value="Search!" onclick="doSearch()">

The "input" tag tells the browser that we're going to provide some way for the user to interact with the page. We tell it the "type" is "button" which will cause the browser to create a press-able button on the page, with the word "Search!" written in it, like this: . (Feel free to create your own label instead of "Search!". Go nuts.)

The "onclick='doSearch()'" tells the browser than when the user presses the button, the browser should look for some JavaScript code called "doSearch." We'll write that code soon.

10. <div id="resultsdiv"></div>

A "div" is another standard tag. It creates a rectangular area on a web page into which goes content that should stay together on the page. In this case, the JavaScript we'll write will use this "div" (with an id of "resultsdiv") as a place to list the results of its search of the the Harvard Library.

1.1. Try out your Web page (and configuring MAMP)

We want to load this new HTML page into a browser to see how it looks. That's a little trickier than any of us would like. For example, simply opening up the Mac Finder or Windows Explorer and double clicking on the file will launch it into your default browser, but the browser won't treat it like a Web file. For that to happen, you have to have a web server present it to the browser.

Let's say that you have installed MAMP (Mac download / Windows beta download). If you followed the installation instructions, it will have installed the Apache web server as well as some other pieces we're going to need. On the Mac, MAMP installs itself into your Applications folder, creating a folder called "MAMP." On Windows it installs itself in TK. (It also creates a "MAMP PRO" folder. Ignore that folder, but do not delete it.) Within MAMP is another folder called "htdocs." That's where you should save all the files we're going to create. So, in "htdocs" create a folder called "myFirstApi" (or whatever) and save the HTML document you just created into that folder under the name "myFirstApiScript.html"

Now let's configure MAMP. I'll assume you loaded it into the default directory. Go to that location and doubleclick on the MAMP program. It will start up. You should see this on the Mac and something similar on the PC:

Both the Apache Server and MySQL Server LEDs should be green. (We don't need MySQL for this project but it won't harm anything.) Click on "Open Start Page" in the MAMP dialogue box and you should get a "Welcome to MAMP page" in your browser. Excellent!

Close that page and go back to the MAMP dialogue box. Click on "Preferences..." and choose the "Ports" tab on the page that opens up. You should see something like this:

Click on "Set to default Apache and MySQL ports."

Save your changes, but keep MAMP open.

Now give it a try by loading your new web page into your browser. But remember to do this by using the address that will tell MAMP to treat your page not like a plain old text file but as a web page full of web instructions and wonders. That might be:

http://localhost/myFirstApiScript/myFirstApiScript.html

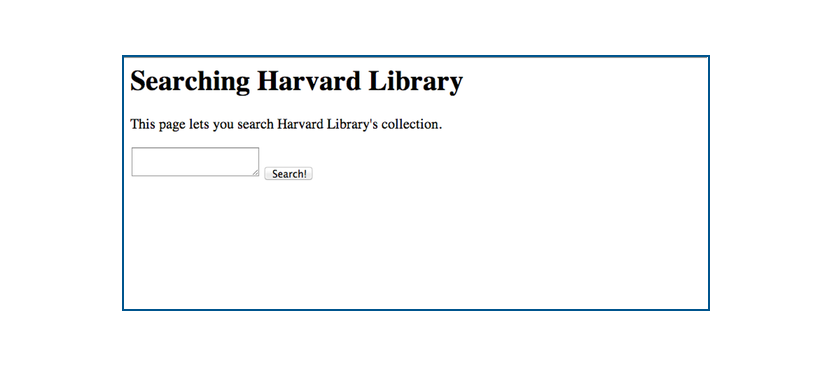

Your browser will now talk to the Apache web server (the "localhost" does that), and that web server will deliver the web page to your browser, so that you see something very much like this in your browser:

If not, check the page in your text editor. Browsers are finicky about some tags that don't have matching closing tags (i.e., the ones with a forward slash in them). They're also finicky about unmatched quotation marks within tags.

Just remember: if you're not seeing roughly what the screen capture above shows, it's your fault.

Section 2: The JavaScript

Start a new file in your text editor and call it "myFirstApiScript.js." The ".js" signifies that this will be a JavaScript file.

JavaScript is a programming language designed to work with HTML documents. It is one of the less scary programming languages.

As with most modern programming languages, it not only knows how to do things (add numbers, remove letters from a string of characters, etc.), it lets the programmer create new functionality -- new things your JavaScript program knows how to do. In our case, we want to create a function called "doSearch" (because that's what we happened to name it in the HTML document) that will search Harvard's collection of library items (books and more) for anything that matches the word that the user has typed into the textarea. This will happen when the user presses the button we created in the web page.

So, into our blank JavaScript document paste the following:

| 1 | function doSearch(){ |

| 2 | // Do the search |

|

| |

| 3 | var searchbx = document.getElementById("searchbox"); // get the searchbox |

| 4 | var searchterm = searchbx.value; // get the search term |

|

| |

| 5 | // if it's blank, give up |

| 6 | if (searchterm == ""){ |

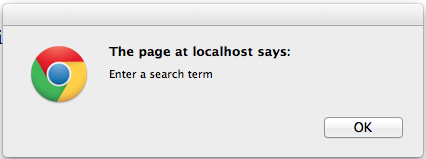

| 7 | alert("Enter a search term"); // put up an explanation for the user |

| 8 | return; // jump out of this funciton |

| 9 | } |

|

| |

| 10 | // Call the PHP script that will do the API call |

| 11 | $.ajax({ |

| 12 | url: 'searchHarvardLibrary.php', |

| 13 | type: 'POST', |

| 14 | data: {search : searchterm}, |

| 15 | success: function(r){ |

| 16 | displayResults(r); |

| 17 | } |

| 18 | error: function(e){ |

| 19 | alert("Something went wrong: " + e); |

| 20 | } |

| 21 | }); |

| 22 | } |

There's a lot going on in here, so let's once again go line by line.

1. function doSearch(){

We create a new function by declaring it with the word "function," then the name we want to give it ("doSearch") followed by a pair of parentheses. (Later we'll see what those parentheses are for.) Notice also the opening curly brace ( { ) and the matching one all the way at the end. The function itself goes between those curly braces.

2. // Do the search

Double forward slashes are comments. Anything after them on a line is ignored.

3. var searchbx = document.getElementById("searchbox"); // get the searchbox

First, note that JavaScripts expects a semicolon at the end of an instruction.

"var" indicates that the next word is a variable. If you've done any programming at all, you know that a variable is a label the programmer makes up to hold some value. In this case, "searchbox" will stand for the textarea in the web page —not the content of the textarea, but everything about the textarea. But to understand the rest of this line, you need to understand the concept of the DOM (document object model).

From the user's point of view, a web page looks like text and graphics laid out on a page. From the browser's point of view, the web page consists of a set of objects that are nested within various containers. The biggest container is the document itself. In our web page, in the document there is an H1, p, textarea, button, and an empty div, in that order. A div is itself a container, and it can contain other containers. So, to the browser, the page looks like a nested set of containers that contain objects — or like a branching tree, as the professionals think of it.

So, the line

document.getElementById("searchbox");

tells the top-level container — the document — to do something it knows how to do: find an element within it that has the ID of "searchbox." (Note the capitalization of "getElementById," especially that last "d". It matters.) The JavaScript then sets the value of the variable searchbx to the textarea that has the ID of "searchbox."

4. var searchterm = searchbx.value; // get the search term

Now we have to ask the textarea to tell us what its contents are. We do that by telling searchbx to do something it knows how to do: give us its value. The variable "searchterm" now contains whatever text the user typed into the text area.

You may have noticed my use of phrases such as "tell us what its contents are" or "ask it to do something it knows how to do." That's because from the browser's point of view, the things on the page are objects. An object is something that comes with certain properties and capabilities. For example, the "<p>" tag creates an object that has properties such as font-size and margins. It has capabilities ("methods," to be technical) such as letting a user select elements. Likewise, the "<textarea>" tag creates an object that knows how to display the text typed in by the user. A textarea doesn't know what to do if you try to paste an image into it. Likewise, a "<p>" doesn't have a way to accept and display keystrokes from a user, which is why you usually can't edit the text on web pages. (Note: Some of this paragraph is slightly inaccurate for the sake of clarity.)

6. if (searchterm == ""){

But suppose the user forgot to type anything into the textarea? Let's check. The parentheses after the "if" contain a condition that can be true or false. If the conditions evaluate to true then the code within the curly braces (lines #7-8) are executed. Otherwise, the browser just skips right over them.

In this case, the test is whether the value of the textarea (i.e., what the user typed in, as captured in the variable "searchterm") has any content. So, if the searchterm equals an empty string of text (""), then the lines between the curly braces will be run.

A couple of notes: As you probably know, a "string" is programming talk for what we would normally call text. Second, notice the double equal signs. This is crucial. If you forget and only put in one equal sign (and everyone makes that mistake more than once), JavaScript won't test whether the variable searchterm has any characters. Rather it will set the variable "searchterm" to a string with no characters. Remember: The "==" means "test this." The "=" means "set this."

So, if the searchterm is empty, then line #7 will pop up a notice that tells the user to enter a search term. Line #9 will end the entire doSearch function. Nothing else will happen.

What happens after this -- the calling of the PHP script -- needs its own section.

2.1. AJAX & jQuery

At line #10, a couple of new concepts collide. Let's take a look.

2.1.1. AJAX

Before AJAX, whenever you interacted with a Web page in a way that required it to go get some more information from its home base — maybe you clicked on one of the movies listed on your local theater's page — the browser would have to reload the entire page. And you would wait. After AJAX, a Web page can ask for some more information and just plop it into the existing page. That makes much more sense.

But the steps JavaScript requires to do an AJAX call are ridiculously complex. Which brings us to our second topic...

2.1.2. jQuery

JavaScript is great, but there are some functions that are a bit unwieldy. And some are seriously unwieldy. Like using AJAX.

So John Resig, an extremely talented and very generous JavaScript coder wrote a bunch of functions in JavaScript that make JavaScript easier to use. Those functions are called jQuery.

Over the years, jQuery has come to include an incredible library of functions that you are free to use as if they were built into JavaScript. For example, you could write a function in JavaScript that will cause a new element on a web page to fade in slowly while increasing in size, but it'd be a lot of work. Or, you could invoke that functionality with a single line of jQuery.

As a reminder, here's the part of our code that does the AJAX work:

| 10 | // Call the PHP script that will do the API call |

| 11 | $.ajax({ |

| 12 | url: 'searchHarvardLibrary.php', |

| 13 | type: 'POST', |

| 14 | data: {search : searchterm}, |

| 15 | success: function(r){ |

| 16 | displayResults(r); |

| 17 | } |

| 18 | error: function(e){ |

| 19 | alert("Something went wrong: " + e); |

| 20 | } |

| 21 | }); |

11. $.ajax({

To tell JavaScript that the code you're using functions from jQuery, you preface it with a dollar sign, as in line #11

In this particular case, we're using jQuery's function for doing an AJAX call.12. url:'searchHarvardLibrary.php',Line #12 tells it to run the PHP script we haven't yet written.

13. type:'POST',Line #13 tells the PHP what's going to be asked of it. Just accept this line. Thank you.

14. data: {search : searchterm},

We're going to have to tell the PHP script what term to search the Harvard Library for, so we pass it that information by telling it that we're sending it a variable called "search" (or whatever we choose) which will have the value contained in the variable "searchterm."

15. success: function(r){

16. displayResults(r);

17. }

Then we tell JavaScript what to do if our PHP script works without generating any errors. If the PHP works ("success:"), JavaScript should jump to a new function, which we have not yet written, and should pass the results of the PHP search to that new function. Those results are in the variable we have chosen to call "r".

18. error: function(e){

19. alert("Something went wrong: " + e);

20. }

If, on the other hand, something's gone wrong with our PHP script's attempt to get data out of the Harvard Library, then we'll pop up a dialogue box that tells the user that something has gone wrong, including a message ("e") about what the error was. "Alert" is JavaScript that creates a popup box.

The ")};" on line #21 ends the multi-line call to the jQuery AJAX function.

Note that if the AJAX call succeeds — if we get any usable results from the LibraryCloud API — the program jumps out of the doSearch function and invokes the yet-to-be-written displayResults function.

Before we write it, let's take a look at the PHP we just invoked.

Section 3: PHP

Create a new file with your text editor and save it into your folder as "searchHarvardLibrary.php".

| 1 | <?php |

| 2 | $searchterm = $_REQUEST['search']; |

| | |

| 3 | $uri = "http://librarycloud.harvard.edu/v1/api/item/?filter=collection:hollis_catalog&filter=keyword:" . $searchterm; |

| | |

| 4 | $file = file_get_contents($uri); |

| 5 | die($file); |

| | |

| 6 | echo $file; |

| 7 | ?> |

1. <?php

The first line declares this to be a PHP file. Don't question this. Just obey.

2. $searchterm = $_REQUEST['search'];

Variables in PHP start with a dollar sign; it has nothing to do with jQuery. So, we create a variable called "$searchterm" and set it to the value that our AJAX script passed to the PHP. The weird PHP phrase "$_REQUEST['search']" retrieves the value we sent with the "search" label.

3. $uri = "http://librarycloud.harvard.edu/v1/api/item/?filter=collection:hollis_catalog&filter=keyword:" . $searchterm;

There's an important point you should know about APIs. Most are accessed exactly the way you access a normal web page. (Such APIs are called RESTful.) So, this line constructs the web address that will work for LibraryCloud. LibraryCloud's API lives at "http://librarycloud.harvard.edu/v1/api/item/". But, of course we have to tell the API exactly what we want from it. So, we put a question mark at the end of the normal address; everything after the question mark are instructions for the API to follow.

The first instruction is that it should limit itself to giving us results from the Harvard Library collection, for LibraryCloud has records from other libraries as well. The Harvard Library collection is known as HOLLIS, so our instruction takes the form of "filter=collection:hollis_catalog." (Why "hollis_catalog" instead of "HOLLIScatalog," or whatever? Because that's what the lead developer of LibraryCloud, Paul Deschner, decided to call it.)

We put in a "&" to add another instruction to tell the API that we want to filter HOLLIS according to the search term represented by the variable "$searchterm." (Note that PHP uses a period instead of a plus sign when it pastes strings of characters together; it saves the plus sign for adding numbers.)

So, if the user entered "evolution" as her search term, the variable $uri will now look like this:http://librarycloud.harvard.edu/v1/api/item/?filter=collection:hollis_catalog&filter=keyword:evolution

(Want to try something fun? Copy and paste that full address into your Web browser. You should get data back.)

4. $file = file_get_contents($uri);

PHP has a command that will get the contents of any web page you point it at. (Well, almost any.) That's what we do here, loading it all into the variable "$file" because the content of the page we've connected to is the data that the API responds with.

5. die($file);

The previous command opened up communication with a Web address. The "die" command shuts it off. If you forgot this line, the Internet would survive.

6. echo $file;

This transfers to our AJAX code the data that we've fetched. If our PHP request failed, an error message would instead be transferred, and the AJAX would count the attempt as an "error," not as a "success."

Section 4. Displaying the results

At this point we've invoked our PHP script which has asked the LibraryCloud API for works that have the user's desired search term somewhere in their record. The API has complied. We have results! Yay!

So, let's go back to our JavaScript and write the displayResults function that's going to show those results on our Web page, making our users oh so happy. But it's going to take some conceptual work to get there.

The first thing we're going to do is to declare displayResults as a function, which we do as follows:

function displayResults(res){

}

The "res" in the parentheses is a variable that contains the value passed to it by the "success" function in the AJAX we just looked at. That's what the parentheses in a function declaration are for: to enable data to be passed into the function.

4.1. The data: JSON

But what data?

We've only gotten to this function because our PHP script asked the LibraryCloud API for all the works in the Harvard Library collection that somewhere in their title, subject, description, etc. use the specified search term. The API has found some works. But because it's conceivable that there could be over a million works with that search term — Harvard has over a million books that have "history" as their subject — the API quite reasonably only returns the first 25. You can always go back for more.

Here's a highly simplified version of information returned by the API:

number_of_items_found: 3,

starting_with_which_item: 0,

filtered_by: [

keyword: "evolution",

]

docs: [

{

title: "Origin of Species",

creator: [

"Darwin, Charles"

]

},

{

title: "Theory of Evolution",

creator: [

"Lupinski, Jane",

"Mattingly, Sarah"

]

},

{

title: "Twentieth Century Evolution",

creator: [

"Smith, Fred",

"Grohl, Chris"

]

}

Remember, that's not JavaScript. It's data. (Well, it's actually data expressed as a JavaScript object. Never mind.) In this example, there are only three works in the Harvard Library that match the search term we queried it about. Here's a diagram of the above:

I've outlined each of the three results (the books that match the search term) in red. All three are listed under the one label "docs," outlined in green. Above the red box is some information that applies to the entire set of results. For example, number_of_items_found tells us that the API found three items. (Note that I've made up some labels for this example.)

This way of expressing data is called JSON (JavaScript Object Notation). It's actually pretty straightforward. JSON represents data as key:value pairs. A key is the label the source (LibraryCloud) applies to the information. The value is the information itself. In the first result in the example above,"title" is a key and its value is "Origin of Species". Likewise, "creator" is a key, and "Charles Darwin" is its value. Easy.

It gets a little more complicated when you notice the values that are between brackets, such as:

creator: [

"Lupinski, Jane",

"Mattingly, Sarah"

],

The brackets indicate that there may be more than one value for the key — a book can have more than one author — so the "creator" key needs to be able to list them all. The technique for doing this is called an "array," which you may well have come across if you have done any programming before. An array is a set of items. In this case, they are a set of authors' names. JavaScript knows how to extract each item from an array, as we'll soon see.

Now let's unleash the dogs of complexity.

When the LibraryCloud API returns information about a work, it returns a lot of information about the work: the author, title, and publisher, of course, but also its physical dimensions, number of pages, which of Harvard's 73 libraries have how many copies, and much more. In fact, here's the information for one book:

docs: [

{

holding_libs: [

"MCZ",

"CAB"

],

lcsh: [

"Coevolution."

],

pages_numeric: 443,

score_holding_libs: 2,

id_isbn: [

"0226797619",

"0226797627"

],

id: "A49C4539-C297-B803-BD26-4F8CDF2497E5",

collection: "hollis_catalog",

title_sort: "geographic mosaic of coevolution",

call_num: [

"QH372 .T482 2005"

],

height: "24 cm",

title_link_friendly: "the-geographic-mosaic-of-coevolution",

creator: [

"Thompson, John N."

],

score_checkouts_grad: 3,

pub_date: "2005",

loc_call_num_subject: [

"Science -- Biology (General) -- Evolution -- Coevolution"

],

pub_location: "Chicago",

pages: "xii, 443 p",

id_lccn: "2004023861",

loc_call_num_sort_order: [

9506794

],

score_checkouts_fac: 6,

data_source: "harvard_edu",

dataset_tag: "harvard_edu_catalog_bibs_1385882476",

shelfrank: 3,

title: "The geographic mosaic of coevolution",

language: "English",

id_inst: "009733508",

id_oclc: "ocm56733182",

note: [

"Includes bibliographical references (p. [371]-425) and index"

],

height_numeric: 24,

format: "Book",

publisher: "University of Chicago Press",

pub_date_numeric: 2005,

source_record: {

9060: "DLC",

988a: "20050802",

504a: "Includes bibliographical references (p. [371]-425) and index.",

245a: "The geographic mosaic of coevolution /",

035a: "ocm56733182",

100a: "Thompson, John N.",

245c: "John N. Thompson.",

650a: "Coevolution.",

440a: "Interspecific interactions",

020a: [

"0226797619 (cloth : alk. paper)",

"0226797627 (paper : alk. paper)"

],

040a: "DLC",

040c: "DLC",

040d: "DLC",

0822: "22",

300a: "xii, 443 p. :",

300b: "ill., maps ;",

300c: "24 cm.",

score_total: "6",

010a: " 2004023861",

042a: "pcc",

260a: "Chicago :",

050a: "QH372",

260b: "University of Chicago Press,",

260c: "c2005.",

050b: ".T482 2005",

082a: "576.8/7"

}

},

Now imagine an array of 25 of these.

The data may be complicated, but JSON is not. It's a bundle of key:value pairs, and some of the values may be arrays of values. That's what our PHP is going to send back to our JavaScript.

Let us therefore return to our JavaScript, which is already in progress.

4.2. Displaying the results: Part 2

We got as far as creating an empty function that's importing the JSON retrieved by the PHP invoked by the AJAX call. Got it?

function displayResults(res){

}

Now let's do something with it.

Here's the complete display function:

| 1 | function displayResults(res){ |

| 2 | // display the results of the query |

|

| |

| 3 | // get the div where the results will be shown |

| 4 | var showdiv = document.getElementById("resultsdiv"); |

| | |

| 5 | // convert the JSON into an array |

| 6 | var results = JSON.parse(res); |

|

| |

| 7 | var title, i; // create a variable or two |

|

| |

| 8 | // cycle through each of the elements of the results array |

| 9 | for (i=0; i< results.docs.length; i++){ |

| 10 | // get the title of the current element in the array |

| 11 | title = results.docs[i].title; |

| 12 | // create a new div for the title and add it to the page |

| 13 | currentcontent = showdiv.innerHTML; // get current content of the div |

| 14 | showdiv.innerHTML = currentcontent + "<div class='oneresult'>" + title + "</div>"; |

| 15 | } |

| 16 | } |

After some comments, we get the first line of working code:

4. var showdiv = document.getElementById("resultsdiv");

Remember in the HTML page we created a "div" (an empty block on the page) with an id of "resultsdiv"? Line #4 finds that div, using "getElementByID" discussed above, and assigns it to the variable "showdiv". (Can you find the error in in the prior sentence? Capital!)

6. var results = JSON.parse(res);

We need to convert the JSON into data that we can more easily use. JavaScript has a function for that: JSON.parse. From this we get an array that contains all of the information in the JSON. We assign that array to the variable "results."

7. var title, i; // create a variable or two

We create variables called "title" and "i" As of now, neither has any value associated with it.

9. for (i=0; i< results.docs.length; i++){

Prepare for trickiness. (Also note that this is not how a professional coder would do it.) We want to look at every result in the JSON. These are in an array with the key "docs." So, this line sets up a loop that works like this:

- Set i equal to zero.

- Check to see if i is less than the number of elements in the docs array.

- If it is less, then execute the lines within the curly brackets and increase the value of i by one ("i++").

- Repeat until the value of i is no longer lower than the number of elements in the array.

Now let's step inside the curly brackets to see the code that is executed for every result our query found.

11. title = results.docs[i].title;

Once you understand the dots, this line will make sense. So, we have stuffed all of the results of our query into a variable called "results." We know that the results we got back contains an array called "docs". And we know that every element in the docs array has a key called "title." The dots tell our script to look inside the results variable. So,

results.docs[i].title

can be read as: Take the variable "results," look at the "docs" array inside of it, look at the particular element of the "docs" array that we're currently cycling through ("i") and grab the value of the "title" key within that element of the "docs" array. (I know that's confusing. It might be easier to think about it if you mentally replace the dots with >'s.)

The first time through this countdown loop, "i" will be equal to 0, which is where the numbering of an array begins. So, this line will grab the first element of the "docs" array. The second time through, i=1, so it will grab the second element. Etc.

Each time through, we're going to add a visible line to the Web page showing the title of a book. Let's unpack line #13.13. var currentcontent = showdiv.innerHTML;

We set the variable "currentcontent" to whatever is the HTML inside the "showdiv" div. The first time through, that div has no content, but thereafter it will contain all of the titles that have been loaded into it.

14. showdiv.innerHTML = currentcontent + "<div class='oneresult'>" + title + "</div>";

Now we're going to add one title to the "showdiv" div. But we want to wrap each of these titles in its own div. (We could get away without doing that.) So we create a div tag, and we give it a class called "oneresult." Then we plop in the title that we've retrieved from the results, and then add the closing tag for the new div.

We are now done with the JavaScript, at least in its most basic form. Only one thing remains.

Section 5. Putting it all together

You've written all the code you need, but the button on your HTML page won't work until you've stitched it together.

All your files should be in one folder, which you might have named "MyFirstApiScript." In there should be:

- MyFirstApiScript.html - your web page

- MyFirstApiScript.js - your JavaScript

- searchHarvardLibrary.php - your PHP script

- a jQuery file...

Ao, about that jQuery file: Go to the download page (jquery.com/download). Or, better, just get the 1.11.02 version by clicking here: 1.11.02. By the time you read this, there will likely be newer versions, ourbut for minimal purposes, this version will be fine. Now, when you click on the 1.11.02 link, it may load a bewildering page of text into your browser. Good. All you have to do is go to your browser menu and click "Save." Save it to the "MyFirstApiScript" folder under the name "jquery-1.11.1.min.js". One way or another, you want a file with that name in your folder.

Now, go back to the web page you built. In your text editor, add the following two lines right after the </title> tag:

<script type="text/javascript" src="jquery-1.11.1.min.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript" src="myFirstApiScript.js"></script>

The first line tells your browser to load the code in the jQuery file. The second tells it to load the code in your JavaScript file.

When you're done, the head portion of your web page should look like this:

<html>

<head>

<title>My first API script</title>

<script type="text/javascript" src="jquery-1.10.2.min.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript" src="myFirstApiScript.js"></script>

</head>

Section 6: Debugging

There's virtually no chance that you did everything right the first time. Nothing personal, but you're a human, right?

Unfortunately, debugging is beyond the scope of this tutorial.

Section 7: Making it better

7.1. Prettying it up

You can make your Web page less ugly by creating a CSS file that tells the page how to format the various elements on it.

First, you have to tell your web page to look for a CSS file. To do that add the following line immediately below the <title> line:

<link type="text/css" rel="stylesheet" href="myApi.css">

Now use your text editor to create a file named "myApi.css" and save it into the same old folder.

CSS is a deep art, but you can get started if you know that it can adjust the formatting of built-in HTML elements such as H1 and P, the formatting of any element that has an ID, or the formatting of elements that share a class. You indicate a built-in element with its name, an element with an ID by putting a "#" in front of the ID, and a class by putting a "." in front of the class.

Here's an example:

H1 {

font-family: "Helvetica Neue," Helvetica, Arial, Verdana;

color: "#0D5BFF";

}

P {

font-family: "Helvetica Neue," Helvetica, Arial, Verdana;

}

#resultsdiv{

background-color: #F6F1FF;

border-width: 1px;

border-style: solid;

border-color: #5EA6FF;

}

.oneresult{

font-family: "Helvetica Neue," Helvetica, Arial, Verdana;

font-size: 12px;

color: #1525FF;

background-color: #C0D6FF;

margin-left: 50px;

}

H1 and P are built-in elements. "#resultsdiv" is a unique element with that ID. ".oneresult" is a class that can be applied to any number of elements.

There's much much much more you can do with CSS. Here's one tutorial. Have fun.

7.2. Extract more information

Our web page only shows the title of the books found by the API. We could extact much more information from the JSON. It's actually quite easy.

Remember the line:

title = results.docs[i].title;

We could just as easily make up a variable to hold the authors names. If you look at the JSON, you'll see that the key for that is "creator" so the following should work:

author = results.docs[i].creator;

Should work. Doesn't work, at least when we go to display it. That's because the value of the "creator" key is an array. So instead we have to do a little more work. Instead of that line, use this:

author = results.docs[i].creator.join("; ");

This extracts the array of creators as in the previous attempt, but this time we've added a "join('; ');" command that tells JavaScript to merge each of the elements of the array, separating them by a semicolon and a space. For example, this array:

[

"Smith, Fred",

"Grohl, Chris"

]

Will become this string of characters:

Smith, Fred; Grohl, Chris

Now that you just have to add this string to the line that contains the title.

Power Hint: You'll probably want to format the titles differently than the authors. So, surround each with a span element, and give those spans appropriate class names. For example, a line might look something like this:

<span class="title">Origin of Species</span>

<span class="author">Charles Darwin</span>

Assign those classes the appropriate formatting via your CSS file.

As for what spans are, that's what Google's for.

7.3. When you have questions

When you can't figure out how to do something, and especially when you're sure you do know how to do it but it's not working, StackOverflow.com is your friend. Millions of stuck developers find succor there. You can ask a question and very likely an anonymous set of developers will pitch in to answer it.

But, before you post a question, search the site. Since the site has answered over three million questions, it's extremely likely -- just about definite -- that your question has already been answered.

And keep in mind that while Stackoverflow is an incredibly useful site, it isn't designed to answer questions peculiar to any one API.

7.4. Share your code

We have no choice but to learn from one another. The code you've created can teach someone else to do what you've done (or possibly how not to do it :) The code you create can be re-used by someone with the same or related need.

So share your code!

There are two steps:

1. Post your code somewhere where people can find it.

2. Indicate in your project that you're providing your code under one of the available open licenses.

There are multiple open licenses you can use. The MIT license and Gnu Public License (GPL) are two of the most commonly used. Here's some text you can paste somewhere in your project (preferably where users won't see it):

-

License Dual licensed under the MIT license (below) and GPL license.

GPL License http://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-3.0.html

MIT License

Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of this software and associated documentation files (the "Software"), to deal in the Software without restriction, including without limitation the rights to use, copy, modify, merge, publish, distribute, sublicense, and/or sell copies of the Software, and to permit persons to whom the Software is furnished to do so, subject to the following conditions:

This permission notice shall be included in all copies or substantial portions of the Software.

THE SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED "AS IS", WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE AUTHORS OR COPYRIGHT HOLDERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH THE SOFTWARE OR THE USE OR OTHER DEALINGS IN THE SOFTWARE.

Somewhere visible, you should proudly let your users know that your work is Open Source.

Thanks for sharing!

8. Beyond LibraryCloud

The basic techniques I've explained here will work with lots of other APIs, although each has its own way of specifying what results you want. To find out, you have to visit their page of documentation.

Some require that you get a special "key" from them that identifies who is doing the asking. Quite often those keys are free, and the documentation will explain both how to get one and how to embed it in the query your PHP sends to the API. For example, check out the excellent documentation for the API of the Digital Public Library of America.

Good luck riding the open range!